Daisaku Ikeda is a Japanese Buddhist philosopher and peace-builder and president of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI) grassroots Buddhist movement (www.sgi.org).

TOKYO, Nov 21 2014 (IPS) – As we approach the 70th anniversary next year of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there are growing calls to place the humanitarian consequences of their use at the heart of deliberations about nuclear weapons.

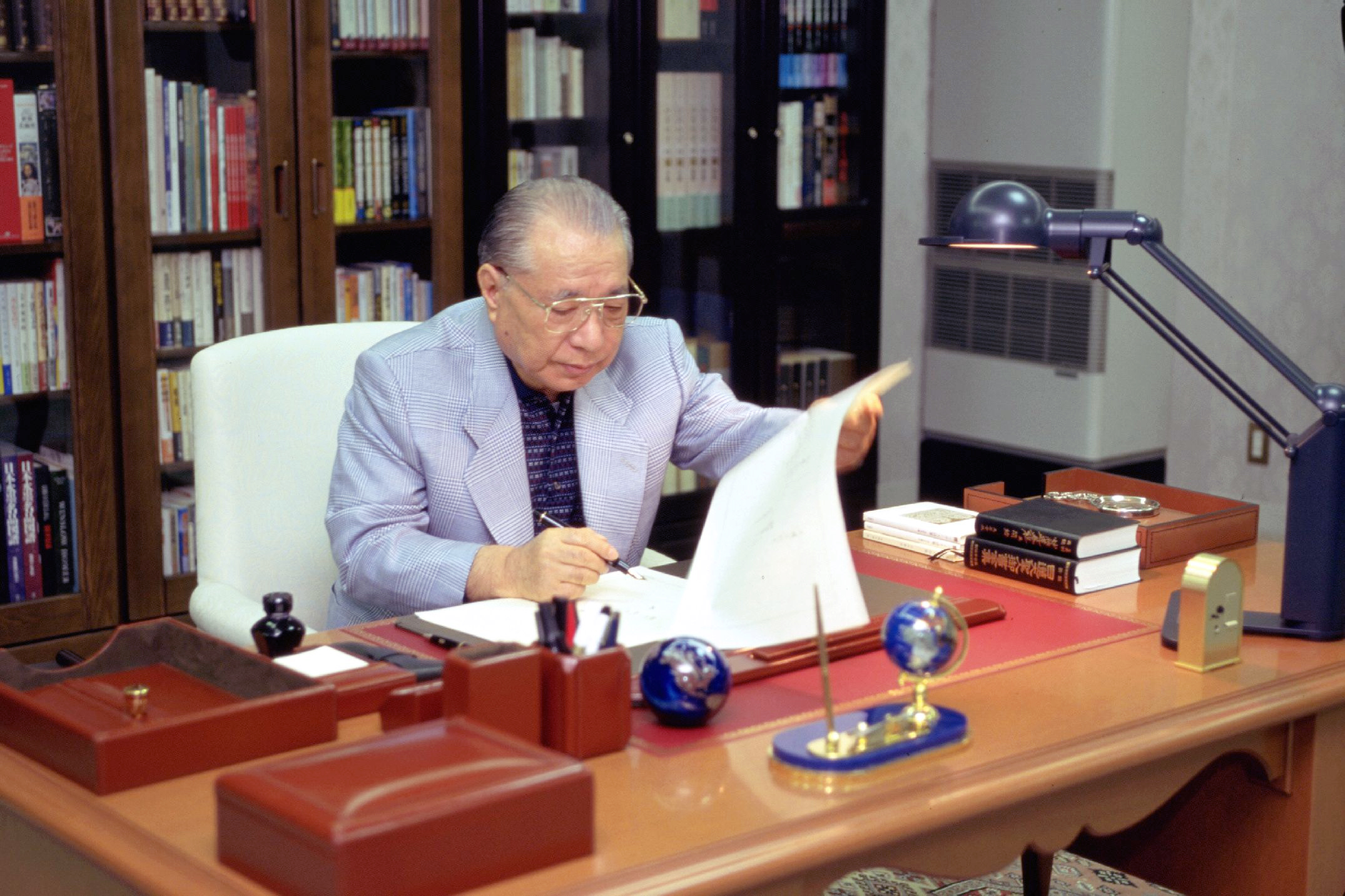

Dr. Daisaku Ikeda. Credit: Seikyo Shimbun

The Joint Statement on the Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons presented to the U.N. General Assembly in October was supported by 155 governments, more than 80 percent of all member states.

The view powerfully expressed in the Joint Statement, that it is “in the interest of the very survival of humanity that nuclear weapons are never used again, under any circumstances,” expresses the deepening consensus of humankind.

The Third International Conference on the Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons will be held in Vienna on Dec. 8-9. This conference and its deliberations should provide further impetus to efforts to end the era of nuclear weapons, an era in which these apocalyptic weapons have been seen as the linchpin of national security for a number of states.

This can only happen when the goal of a nuclear-free world is taken up as the shared global enterprise of humanity with the full engagement of civil society.

Within the agenda of the Vienna Conference, there are two items in particular that require us to adopt the perspective of a shared global enterprise.Today, if a missile carrying a nuclear warhead were to be accidentally launched, there could be as little as 13 minutes before it reached its target.

The first is the examination of risk drivers for the inadvertent or unpredicted use of nuclear weapons due to human error, technical fault or cyber security.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, people were transfixed in horror as the world teetered on the edge of full-scale nuclear war. It took the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union 13 days of desperate effort to defuse the crisis.

Today, if a missile carrying a nuclear warhead were to be accidentally launched, there could be as little as 13 minutes before it reached its target. Escape or evacuation would be impossible, and the targeted city and its inhabitants would be devastated.

Further, if such an inadvertent use of a nuclear weapon were met with retaliation of even the most limited form, the impact on the global climate and ecology would result in a “nuclear famine” that could affect as many as two billion people.

The use of a single nuclear weapon can obliterate and render meaningless generations of patient effort by human beings to create lives of happiness, to create societies rich with culture. It is in this unspeakable outrage, rather than in the numerical calculation of the destructive potential of nuclear weapons, that their inhuman nature is most starkly demonstrated.

The second agenda item that will bring into sharp focus the uniquely horrific nature of nuclear weapons—the aspect that makes them fundamentally different from other weapons—is the impact of nuclear weapons testing.

The citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not the only people to have directly experienced the horrendous effects of nuclear weapons. As the shared use of the term “hibakusha” indicates, large numbers of people continue to suffer from the consequences of the more than 2,000 nuclear weapons tests that have been carried out to date.

Further, communities near nuclear weapons development facilities in the nuclear-weapon states have experienced severe radiation contamination, and there are ongoing concerns about the health impacts on those who have worked in or lived near these facilities.

As these examples demonstrate, the decision to maintain nuclear weapons—even if they are not actually used—presents severe threats to people’s lives and dignity.

Annual global expenditures on nuclear weapons are said to total more than 100 billion dollars. If this enormous sum were to be directed not only at improving the lives of the citizens of the nuclear states, but at supporting countries where people continue to struggle against poverty and inadequate healthcare services, the benefit to humankind would be immeasurable.

To continue allocating vast sums of money for the maintenance of a state’s nuclear posture runs clearly counter to the spirit of the UN Charter, which calls for the maintenance of international peace and security with the least diversion for armaments of the world’s human and economic resources—a call echoed in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Further, we must face squarely the inhumanity of perpetuating a distorted global order in which people whose lives could easily be improved are forced to continue living in dangerous and degrading conditions.

By taking up these two crucial themes, the Vienna Conference will place in sharp relief the underlying essence of the threat humankind imposes on itself by maintaining current nuclear postures—through the continuation of this “nuclear age.” At the same time, it will be an important opportunity to interrogate security arrangements that rely on nuclear weapons—and to do so from the perspective of the world’s citizens, each of whom is compelled to live in the shadow of this threat.

In 1957, in the midst of an accelerating nuclear arms race, second Soka Gakkai president and my personal mentor Josei Toda (1900–58) denounced nuclear weapons as a threat to people’s fundamental right to existence. He declared their use inadmissible—under any circumstance, without any exception.

The SGI’s efforts, in collaboration with various NGO partners, find their deepest roots in this declaration. By empowering people to understand and face the realities of nuclear weapons, we have sought to build a solidarity of global citizens dedicated to eliminating needless suffering from the face of the Earth.

The impassioned wish of the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—and of all the world’s hibakusha—is that no one else will have to suffer what they have endured. This determination finds resonant voice throughout civil society in support for the Joint Statement adopted by 155 of the world’s governments.

Even with governments whose understanding of their security needs prevents open support for the Joint Statement, there are real concerns about the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons.

I trust the Vienna Conference will serve to create an enlarged sphere of shared concern. This should then lead to the kind of shared action that will break the current stalemate surrounding nuclear weapons in the months leading up to the 70th anniversary of the world’s only uses of nuclear weapons in war.

Edited by Kitty Stapp