LONDON (IPS) – It’s peak holiday season across Europe and North America, and people are hitting the beaches and crowding into city centres in ever-increasing numbers. They’re part of a huge industry: last year, travel and tourism’s share of the global economy stood at US$10.9 trillion, around 10 per cent of the world’s GDP.

But residents in tourist destinations are keenly aware of the downsides: overwhelming visitor numbers, permanent changes in their neighbourhoods, antisocial behaviour, strained local services, environmental impacts including litter and pollution, and soaring housing costs.

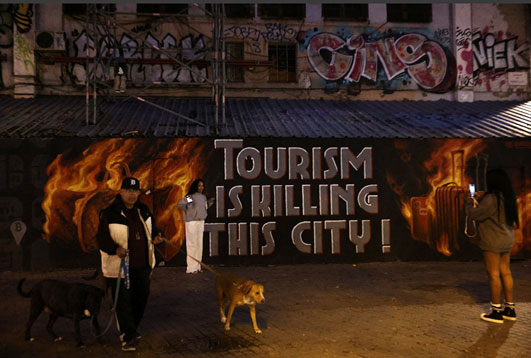

Overtourism occurs when the industry systematically impacts on residents’ quality of life. It’s a growing problem, reflected in recent protests in several countries, with grassroots civil society groups demanding more sustainable approaches.

Residents’ protests

June brought coordinated protests across Europe. In Barcelona, a city of 1.6 million people that receives 32 million visitors a year, the Neighbourhood Assembly for Tourism Degrowth organised a protest that saw people tape off hotel entrances, set off smoke bombs and fire water pistols. In Genoa, protesters dragged a replica cruise ship through the medieval centre’s maze of alleys to highlight the impacts of cruise tourism. Actions had been coordinated at a meeting in April between representatives from France, Italy, Portugal and Spain, who formed the Southern European Network Against Touristification.

These weren’t the first protests. Thousands took to the streets in Spain’s Canary Islands in May, while last year people protested in several European cities. Most recently, residents of Montmartre in Paris hung banners outside their houses pointing out how overtourism is changing their neighbourhood.

Civil society groups are taking action beyond protests. In the Netherlands, residents’ group Amsterdam Has a Choice is threatening legal action against the city council. In 2021, following a civil society-led petition, the council set a limit of 20 million overnight tourist stays a year. But research shows this limit has consistently been exceeded. Now the group could take the city to court to enforce it.

People are protesting across multiple countries because they face the same problem: overtourism is changing their communities and, increasingly, driving them away.

Overtourism impacts

Tourism may create jobs, but these are often low-paid or seasonal jobs with few labour rights or opportunities for career progression. In places with intensive tourism, everyday businesses that residents rely on are often replaced by those oriented towards tourists, with established firms squeezed out by high rents.

Environmental impacts may hit residents while tourists are protected from them: campaigners in Ibiza complain that water shortages mean they’re subject to restrictions, but hotels face no such limitations. Common areas residents once relied on, such as beaches and parks, can become overcrowded and degraded. Ultimately, communities can be turned into stage sets and sites of extraction, impacting on crucial matters of identity and belonging. That’s why one movement in Spain calls itself ‘Less Tourism, More Life’.

Housing costs are a major concern in overtourism protests. In many countries, the costs of buying or renting somewhere to live are soaring, far outstripping wages. Young people are particularly hard hit, forced to hand over ever-higher proportions of their income in rent. Tourism is driving the increasing use of properties for short-term holiday rentals instead of permanent residences. People who live in tourist hotspots have seen once-viable homes bought as investments for short-term lets, causing a loss of available housing and driving up the price of what’s left.

People who live in apartment blocks that have largely become used for short-term rentals complain of their communities being hollowed out: they lack neighbours but frequently have to put up with antisocial behaviour. The sector is often underregulated, and landlords may find regulations easy to ignore and taxes easy to avoid. Spain alone has an estimated 66,000 illegal tourist apartments.

Action needed

Overtourism protests hit the headlines last year when a group sprayed water at tourists in Barcelona. But in the main, protesters are making clear they don’t want to target tourists and aren’t motivated by xenophobia. They want a fair balance between tourists enjoying their holidays and locals being able to live their lives. They want those who reap tourism’s profits to pay their fair share to fix the problems.

Protests are having an impact, with authorities taking steps to rein in holiday rentals. Last year a Spanish court ordered the removal of almost 5,000 Airbnb listings following a complaint that they breached tourism regulations. The mayor of Barcelona has announced plans to eliminate short-term tourist rentals within five years by refusing to renew licences as they expire. Authorities in Lisbon have paused the issuing of short-term rental licences, and those in Athens have introduced a one-year ban on new registrations. That still leaves plenty of regulatory gaps across many countries, and national and local governments should engage with campaigners to further develop regulations.

Many local authorities have also implemented tourist taxes, while Venice has started to charge a peak-season access fee for non-residents and Athens now assigns time slots as a way of managing numbers at the Parthenon. It’s important that taxes and charges aren’t used simply to extract more cash from tourists or dampen demand; money generated must directly help affected communities and mitigate the harm caused by overtourism.

Authorities also need to be more careful about the marketing choices they make and consider whether they’re promoting tourism too widely. Marketing campaigns should try to sensitise visitors about the impacts they can have, and to make choices that minimise them.

Movements campaigning against overtourism are sure to grow, connecting groups concerned about environmental, housing and labour issues as the problem worsens, and as climate change places even greater strain on scarce resources. Overtourism concerns are ultimately an expression of frustration with a bigger problem – that economies don’t work for the benefit of most people. States and the international community must urgently grapple with the question of how to make economies fairer, more sustainable and less extractive – and they must listen to the movements against overtourism that are helping sound the alarm.

Andrew Firmin is CIVICUS Editor-in-Chief, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.

INPS Japan/IPS UN Bureau Report