ANALYSIS: 4 Things I Learned in 14 Days in Japan

NAGASAKI (INPS Japan) — At peak cherry blossom season in April, I spent 14 beautiful days exploring the Catholic Church in Japan by wing and foot, metro and bullet train. I began with Archbishop Tarcisius Isao Kikuchi at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo on the eve of his ad limina visit with Pope Francis in Rome and ended with a prominent Shinto priest, Mitsui Shinsaku, who will attend a September peace conference organized by the Community of Sant’Egidio.

Statistics alone say little. Out of a population of approximately 125 million people, about 536,000 are Catholic. Another 500,000 Catholics work in Japan, sometimes for many years. Fifteen dioceses including three archdioceses (Nagasaki, Osaka, and Tokyo) embrace 850 parishes served by one seminary.

Delicate and unbreakable … humble and proud … Japanese culture and society balance oppositions. Among so many impressions, I distilled four realities about the Catholic Church in the Land of the Rising Sun to share: New Catholics are part of an increasingly multi-cultural society; Catholic schools magnify Church influence; Jesuits brought the faith to Japan in 1549 and still have clout; and peace is a shared agenda fusing Vatican and Japanese worldviews.

Immigration Factor

A cliché about the Catholic Church in Japan is that it’s small, and bound to get smaller, based on the country’s overall demographic decline. The country’s population is disappearing: According to government data, Japan loses 2,293 people a day, clearly an existential crisis.

Tragically, Nagasaki is the world’s fastest declining city. Meanwhile, the government seems to prioritize building its military over incentives for national survival. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida more than doubled the military budget to $56 billion while allocating $25 billion for child care.

But the Church is more dynamic than appears on paper. Japan is an increasingly multicultural nation and many recent arrivals are Catholic.

“More and more, the Catholic Church in Tokyo is universal, meaning, in this place we meet Catholic faithful from around the world,” observed Jesuit Father Antonius Firmansyah, a theology professor at Sophia University, the country’s oldest Catholic university, founded in 1913.

“The church next door [St. Ignatius Church] is very alive with so many countries and ethnicities. The largest number now is Vietnamese [some 520,000 Vietnamese live in Japan today]. The Catholic Church is flourishing because we are really open to working together with different cultures,” said Father Firmansyah, a native Indonesian.

He came to Japan in 2002 and spent his first two years studying the language, explaining, “You cannot touch the heart of Japanese people without using proper terminology.”

According to the lively priest, who also helps lead the university’s Jesuit Center, many Catholics come to Japan from around the world on employment contracts. They might not become citizens, but they often stay for many years, integrating into the nation’s life.

Apropos of immigration, Archbishop Kikuchi told me.

“When I met Pope Benedict for the first time, in 2007, he asked me, ‘What is your hope in your diocese?’” he said. “What came into my mind was the existence of Filipino immigrants. They are married to Japanese farmers because farmers can’t find Japanese wives so they ook for wives among Filipinas, who are Catholic!”

He continued, “These Catholic women reside in villages where we don’t have churches. That is hopeful — wives as missionaries coming to Japan. Cardinal Tagle from the Philippines said the same thing. He encourages Filipino migrants, ‘You are the missionaries, sent by God!’ And it is true.”

Father Firmansyah thinks the Church’s historic missionary approach continues to serve the Gospel message well: “St. Francis Xavier, who brought the Church to Japan in 1549, was very fruitful. He focused on dialogue. It’s a harmonizing process rather than a conquering process.”

When I asked Filipino people where they worship, it became clear that the Filipino church in Tokyo is St. Anselm Meguro Catholic Church, where Mass is offered in Tagalog, Indonesian, English, and Japanese. Rector Father Antonio Camacho was born in Mexico City and came to Japan in 1991 to study theology. Assistant priest, Father Martin Akwetie Dumas grew up and was ordained in Ghana in 2010. He was sent by his order, Society of the Divine Word, to Japan.

While in Kyoto, the country’s beautiful ancient capital, I was initially distressed to attend Mass at the Cathedral of St. Francis Xavier, with some 70 other believers, where the only person on the altar was an Indian nun.

“Our three priests are busy today,” Carmelite Missionary Sister Tesi George told me crisply after Mass. “They already consecrated the hosts,” so it was a Communion service, not Mass.

Influence Through Education

It’s a truism in mission lands that Catholic influence is magnified through the schools it runs from preschool through university. Japan is a case in point.

Archbishop Kikuchi’s mother taught at a Catholic kindergarten in the northern city of Miyako where, he says, “The kindergarten was more famous than the Church.”

He explained, “It has been the policy of the Japanese Catholic Church to utilize education as a tool of evangelization for many years and it has worked. Graduates are in government offices and corporations, so it is important that we have schools such as Sophia, which is a prestigious university.”

It’s the first day of a new school semester when I visit Sophia University’s handsome campus in a bustling Tokyo neighborhood. The school was Pope Pius X’s idea. He gave German Jesuits the directive to start an educational institution in Japan in 1906.

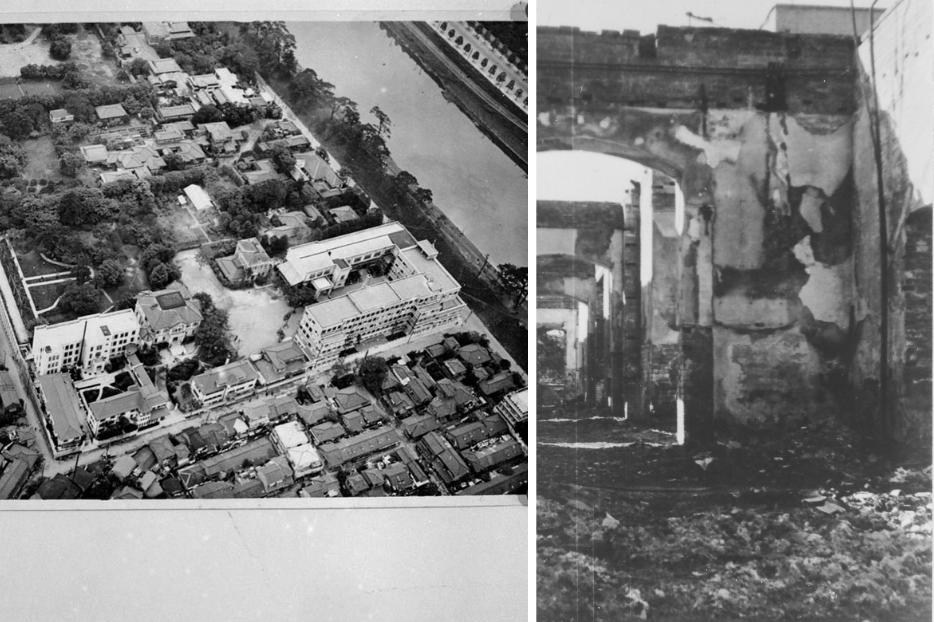

Although much of the campus was flattened by U.S. bombing raids during World War II, it was rebuilt afterward. Today some 14,000 students from more than 80 countries study there.

“The Catholic Church is considered part of Japanese society, especially because of the schools,” observed professor Maria Lupas, an American teaching English language and literature at Sophia. She points out that the mother of Japan’s current emperor, Naruhito, was educated at Catholic schools and graduated from Sacred Heart University, a Tokyo women’s college. Empress Michiko reigned from 1989-2019 and was the first commoner to marry into the imperial house.

Another Sacred Heart graduate is Sono Ayako, a Japanese Catholic who is one of the country’s most respected novelists. Ayako wrote a historical novel Miracles(1973) about St. Maximillian Kolbe, who founded a monastery in Nagasaki and lived there from 1930-36.

Jesuit Impact

St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, planted the Church in Japan in 1549. Faith spread rapidly until the central authority began harsh persecution. Despite an almost 300-year gap between arriving and returning, the Society of Jesus’s impact remains strong to this day.

Besides Sophia, the Society of Jesus also runs a music college in Hiroshima and four prestigious secondary schools.

The order seems to be a keeper of Church history on the archipelago. Jesuit Father Shinzo Kawamura discovered an extraordinary letter of appreciation written to Pope Paul V in the early seventeenth century by Japanese Catholics in the north.. They were responding to a letter of encouragement sent by the Pope to the new faithful. “Our history here is tenacious,” Father Kawamura quietly observed in his Sophia library workspace.

The letter is surprising, among other reasons, because Catholicism is most often associated with trading ports in the south. But as Archbishop Kikuchi explained, Catholicism spread throughout the country, although the southern region has most publicly preserved the story of “hidden Christians.”

Father Kawamura’s research benefited from “Vatican & Japan: The 100 Year Project,” supported by the Kadokawa Cultural Promotion Foundation. For Expo 2025 to be held next April-October in Osaka, the foundation has arranged to bring the Vatican’s only Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, for public display.

Of approximately 150 Jesuit priests in Japan today, over half are senior citizens, many very vibrant.

One of the most inspiring people I met was an 89-year-old priest, Jesuit Father Aldo Isamu, who first came to Japan in 1958 from Salamanca, Spain — and has lived in the country since, even adopting Japanese citizenship which made Father Isamu’s ability to function easier in unexpected ways. The priest became involved in efforts to help “boat people” from Vietnam experiencing discrimination, which led to his first visit to Vietnam in 1990. Soon after, he organized a foundation, “Japan-Vietnam,” to support economic development projects in poor regions, ranging from buying bikes for rural kids to reach school to creating a “cow bank” for poor people to gain sustainable resources. He is planning his 37th trip in September.

Father Isamu says the Church in Vietnam is thriving, in part because local priests find ways to coordinate constructively with local officials. “After the war, 10 Jesuits were jailed. The Church was linked to the enemy. Today, there are almost 300 Jesuits in Vietnam” and the country produces priests serving around the world, including in Japan.

Another wise and dedicated Jesuit I met was Father Renzo De Luca, director of the Twenty-Six Martyrs’ Museum and Monument in Nagasaki. Like Father Isamu, he left his home country (Argentina), and hardly looks back, celebrating 40 years in Japan next year. Father De Luca patiently walked me through the impressive museum, documenting the story of Christianity, persecution, and “hidden Christians” who preserved the faith for some 250 years without priests.

Father De Luca also represents the “small world” aspect of the Catholic Church: while in seminary at San Miguel, his rector for almost three years was Padre Jorge Bergoglio, who encouraged him to become a missionary. Father Bergoglio sent De Luca, at a relatively young age, to Georgetown University to learn English, explaining, “You’ll need it.” Then, the future Pope Francis sent five students to Japan, including Father De Luca.

During the Pope’s 2019 visit, Father De Luca served as his translator. In video of the trip, one sees the younger priest protecting his elder from wind and rain.

Messages of Peace Unite Popes Across Time

For a country where Catholicism is supposedly minuscule, the Church and her popes generate significant good will, especially since Pope John Paul II’s visit in February 1981 as a “pilgrim of peace.”

John Paul II poured himself, spiritually and emotionally, into public addresses in Hiroshima and Nagasaki the two cities attacked by atomic weapons on Aug. 6 and 9, respectively. A contemporary account said the saint’s eyes “sometimes filled with tears” as Hiroshima’s mayor described the bombing’s human horror.

He delivered an emotion-filled appeal for peace at ground zero there, opening with a bald condemnation of war: “War is the work of man. War is destruction of human life. War is death…

Remembering the past is committing to the future. To remember Hiroshima is to abhor nuclear war. To remember Hiroshima is to commit to peace. To remember that the city’s people have suffered is to renew our faith in humankind, the ability to do good, the freedom to choose what is exemplary, and the determination to turn disaster into a new beginning.”

Observed a New Yorker writer who was there, “He spoke in nine languages, starting and ending in Japanese, and in between speaking English, Chinese, French, and Russian — the languages of the five largest nuclear powers — to make sure that there was a sound bite for each country.”

Twenty-eight years later, Pope Francis returned to the same three cities (he flew from Tokyo to Nagasaki then, briefly, to Hiroshima), reserving his most prophetic address for Nagasaki. He lauded Japanese bishops for launching an appeal for the abolition of nuclear arms, bemoaned the “erosion of multilateralism,” and recited the Prayer of St. Francis. The pilgrimage theme was “Protect All Life,” ranging from protecting the unborn, elderly, refugees, and the environment to support a campaign to end capital punishment.

In 2019, the Japanese public seemed even more engaged with the Pope’s words and itinerary than they were in 1981, according to news reports.

“Francis continued John Paul II’s message,” said Father Firmansyah. “Both popes invited the Church in Japan to become a message of peace and really, that is what we are trying to do.”

Added Father De Luca, “Francis was very aware of being a visitor in a non-Christian country. He spoke so all could understand him, and the people were very responsive.”

INPS Japan/National Catholic Register

Victor Gaetan Victor Gaetan is a senior correspondent for the National Catholic Register, focusing on international issues. He also writes for Foreign Affairs magazine, The American Spectator and the Washington Examiner. He contributed to Catholic News Service for several years. The Catholic Press Association of North America has given his articles four first place awards, including Individual Excellence, over the last five years. Gaetan received a license (B.A.) in Ottoman and Byzantine Studies from Sorbonne University in Paris, an M.A. from the Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy, and a Ph.D. in Ideology in Literature from Tufts University. His book God’s Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy, and America’s Armageddon was published by Rowman & Littlefield in July 2021. Visit his website at VictorGaetan.org. This article was republished with permission from the National Catholic Register.