TOKYO, Apr 4 2012 (IPS) – In recent months, the dispute over the nature and intent of the Iranian nuclear development programme has generated increasing tensions throughout the Middle East region. When I consider all that is at stake here, I am reminded of the words of the British historian Arnold Toynbee, who warned that the perils of the nuclear age constituted a “Gordian knot that has to be untied by patient fingers instead of being cut by the sword.”

Amidst growing concerns that these tensions will erupt into armed conflict, I urge the political leaderships in all relevant states to recognise that now is the time to muster the courage of restraint and seek the common ground on which the current impasse can be resolved. The use of military force or other forms of hard power can never produce a lasting solution. Even if it may seem possible to suppress a particular threat, what is left behind is an even more deadly legacy of anger and hatred.

It is a sad constant of international politics that as tensions rise so do the levels of threat and invective that are exchanged. Recall how, when U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev met in Vienna at the height of the 1961 Berlin Crisis, the latter is recorded as saying, “Force will be met by force. If the U.S. wants war, that is its problem. The calamities of a war will be shared equally.”

But we must not lose sight of the fact that, if war breaks out, it is the untold number of ordinary citizens that will bear the brunt of the suffering. This is something that the generations who lived through the wars of the 20th century know from painful experience. In my case, I lost one of my older brothers in battle and we were burned out of our home twice. I retain vivid memories of leading my younger brother, still a young child, by the hand as we fled through the bombs of an air raid. Any use of weapons of mass destruction would magnify and make irreparable this death and mayhem to an unimaginable degree. Nuclear weapons, in particular, must be recognized as weapons of ultimate inhumanity.

In both the Berlin Crisis and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the leaders of the two superpowers finally stepped back from the brink of conflict. In the midst of unbearable tensions, they no doubt saw the devastation that awaited their failure to defuse the situation.

In our present-day situation, we know that a military strike against the nuclear facilities of Iran would be intensely destabilising.

Retaliation would be inevitable, and it is impossible to predict the repercussions in a region now undergoing sweeping political transformation.

Even though the dynamics of international politics seem locked in a spiral of threat and mistrust, we must not ignore the voices of the countless individuals living in the region who desire to see it freed from all nuclear weapons. These can be heard, for example, in research released by the Brookings Institute last December, which found that, by a ratio of two to one, Israelis support an agreement that would make the Middle East a nuclear-weapon-free zone, including Iran and Israel.

The international conference scheduled for this year on establishing a Middle East zone free of weapons of mass destruction is an attempt to respond to the aspirations of the region’s peoples, and all efforts must be made to ensure its success. The elimination of all weapons of mass destruction from the region represents a path toward meeting the common security interests of both Iran and Israel and of the entire region. The efforts of Finland to host this conference have been laudable and I hope that Japan, as a country that has experienced the effects of nuclear weapons in war, will play a positive role in creating the conditions for dialogue.

President Kennedy, having dealt with two potentially apocalyptic crises, once stated: “Our hopes must be tempered with the caution of history.” To date, aspirations for a world without nuclear weapons have been fostered and forged through the unrelenting efforts of those who have met and surmounted the trials of crisis. The process that produced the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which established the first nuclear-weapon-free zone in a populated region, for example, was given new urgency by the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Despite cynical dismissals that such efforts were a waste of time, that there would never be agreement on such a treaty, the negotitors persisted. Today, all 33 states in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the five declared nuclear-weapon states, are parties to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.

In order to resolve the crisis currently hanging over the Middle East, there must be a renewed determination within international society never to abandon dialogue, a deepened conviction that what now seems impossible can indeed be made possible. No matter how daunting the present realities or how treacherous the path forward, we must remember that hope is fostered only through ceaseless, tenacious efforts for peace.

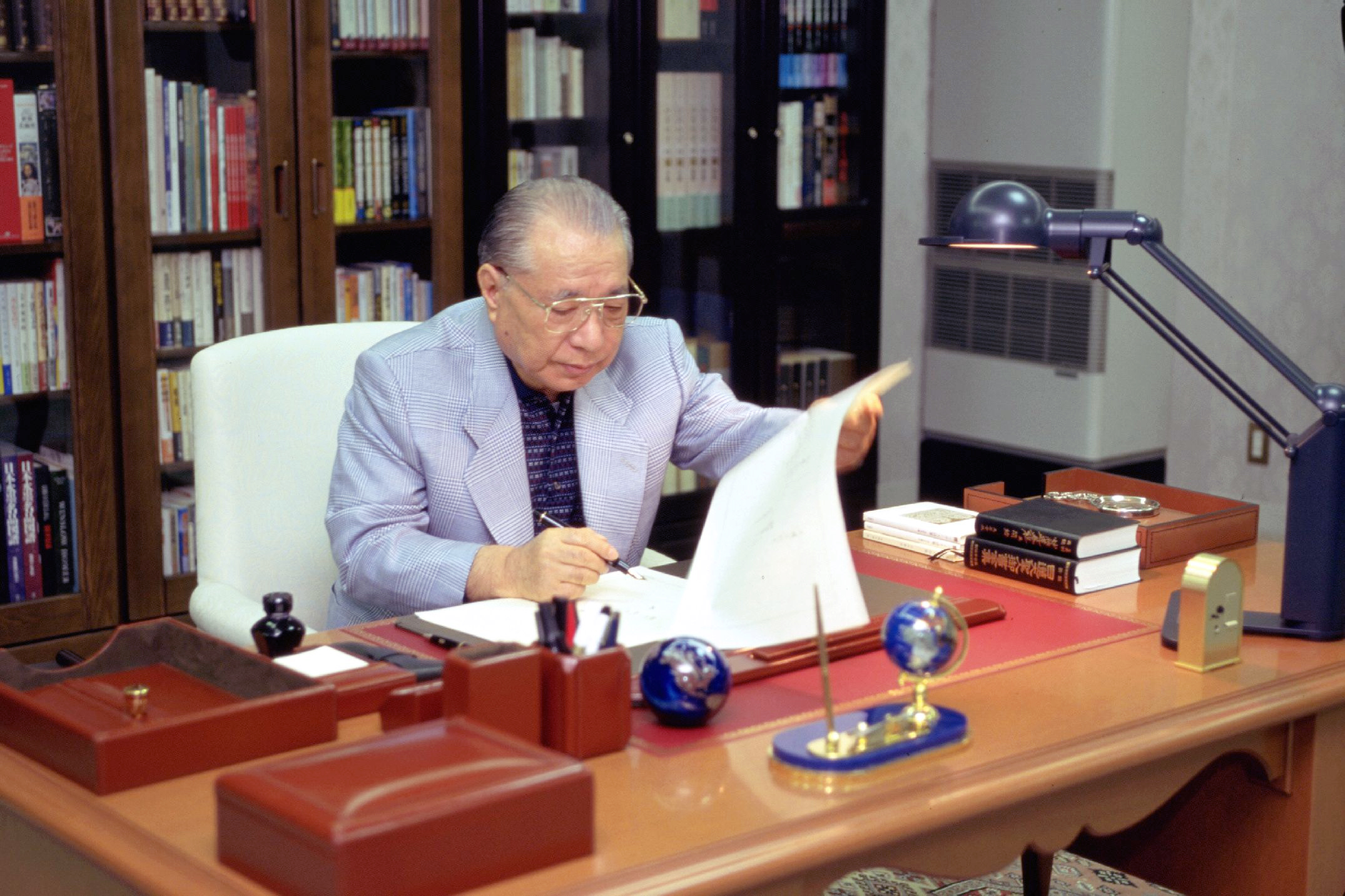

(*) Daisaku Ikeda is a Japanese Buddhist philosopher and peacebuilder and president of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI).