By Edwin Musoni

KIGALI , Apr 7 2013 (IPS) – Bernard Kayumba, the mayor of Karongi district in western Rwanda, remembers just what it was like to be caught up in the genocide that claimed the lives of almost one million people in 100 days 19 years ago.

While there are no conclusive figures of the number of people killed, it is estimated that 800,000 minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus lost their lives in the massacre that began after a plane carrying Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana and his Burundian counterpart, Cyprien Ntaryamira, was shot down over Rwanda’s capital Kigali on Apr. 6, 1994.

Most of the dead were Tutsis, and most of those who perpetrated the violence were Hutus. But according to a report titled “Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda”, published by Human Rights Watch in 1999: “Many Tutsi who are alive survived because of the action of Hutu, whether a single act of courage from a stranger or the delivery of food and protection over many weeks by friends or family members.” Karongi, which was formerly known as Kibuye prefecture, was the site of two massacres in 1994 that resulted in the deaths of thousands of people over just a few days.

Many fled to the town for shelter in its churches and schools. But some 30,000 Tutsis fled to the hills of Bisesero, about 40 kilometres from the town, in the hope of escaping the violence.

Kayumba was one of them. But while there is no official death toll of the massacre there, it is believed that tens of thousands of people were killed in those hills. Kayumba survived.

He was 19 at the time, but he has not forgotten the massacres and their aftermath.

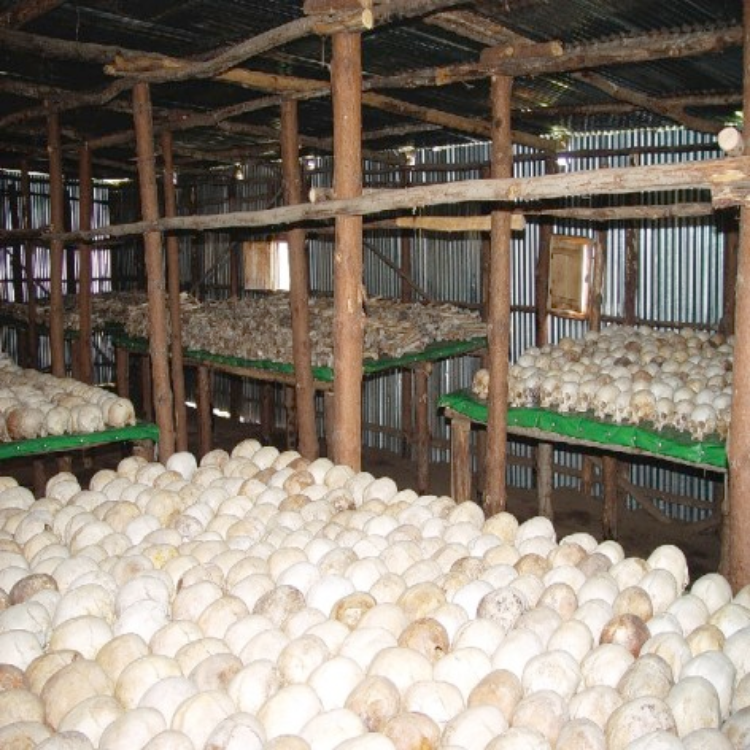

Rwandan genocide survivors exhuming the bodies of their relatives killed and buried in a mass grave during the 1994 100-day massacre. Credit: Edwin Musoni/IPS

“I know what it means to miss school, I know what it means to be hungry myself. So when I am allocating support to the vulnerable in my district (as mayor), I am the most impartial,” he told IPS as the country starts its commemoration week of the genocide from Apr. 7 to 13.

Kayumba said he is mayor of Karongi today thanks to the assistance he received for his university fees from the government project, the Genocide Survivors Support and Assistance Fund, known by its French acronym, FARG.

The fund was set up by the government in 1998 to support the almost 300,000 genocide survivors and receives about six percent of Rwanda’s annual budget.

“I am thankful indeed, because FARG made me what I am today. The fund paid my university school fees. Without it, I don’t know what I would have become,” Kayumba said.

Since its establishment, FARG has spent a total of 127 million dollars, mostly in tuition fees for the 68,367 pupils in secondary schools and more than 13,000 students in higher learning institutions that it supports.

The Rwandan government only introduced free primary and secondary education here in 2010. And according to the United Nations Children’s Fund, about 60 percent of the country’s population lives below the poverty line of 1.25 dollars a day.

The fund also aids survivors with access to health care, while providing new homes and social assistance.

However, it has not been without its controversies. There have been reports of mismanagement of the fund.

In 2011, the local New Times newspaper reported that FARG was forced to drop some 19,000 beneficiaries – 30 percent of the total beneficiaries at the time – who were found not eligible.

It has also come under scrutiny for the quality of its housing projects.

In 2011 the Rwandan Auditor General said the homes were not worth the money spent by FARG on their construction. The audit had been carried out between 2006 and 2007 and the report had also stated: “A significant number of genocide survivors and other targeted needy people who had been earmarked to benefit from this funding still need help with shelter since some of them did not actually benefit.”

However, fund officials said that of the 300,000 genocide survivors, all but 500 families had been provided with new homes. They said that by December 2013, the remainder would have their homes. Fund officials also told IPS that of the 40,000 houses that have been built for survivors, 15,000 were built with money from FARG. The rest were built by government sponsors, which include NGOs, embassies and churches.

“Some houses were built in a hurry in 1995 by well-wishers since providing shelter was a big priority, so not as much attention was placed on the contractors’ (quality of work),” Theophile Ruberangeyo, the director general of FARG, told IPS.

“We also agree that we were cheated in 2003 when entrepreneurs just could not deliver good services while building our houses,” he said of the claims of badly constructed homes.

Jean Pierre Dusingizemungu, the president of IBUKA, an umbrella of genocide survivors’ associations and a high-profile lobby group, told IPS that many people were moving on with courage and determination. Ibuka means “remember” in the local Kinyarwanda language.

“Survivors have learnt that hatred and discrimination lead to death. So they have chosen the better way of building a united community for a brighter future of this nation,” he said.

But this is not the case for all. Some survivors still live with the trauma, anger and fear of what happened to them. Josée Munyagishari, 51, from Murambi in western Rwanda, was speared in the back of her neck in 1994 during the violence. The injury left her paralysed. She was also forced to have her right leg amputated – it had developed an infection after she was attacked with a machete.

“I got treatment, I got a house, my son is getting free education but all this cannot bring back my leg, neither can it make me stand on my legs,” Munyagishari told IPS. Her three-room house was constructed by FARG and her son benefits from the fund’s tuition scheme. But it is obvious that this has not been enough to heal the past.

“The people who did this to me were released from jail and since then I have had nightmares. I see them coming to kill me,” she said, pointing to a house about 100 metres away from her own home, where the accused apparently live.