Viewpoint by Dr Jargalsaikhan Enkhsaikhan

The writer is Chairman of Blue Banner NGO, Former Mongolian Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

ULAANBAATAR (IDN) — Post-cold war peace dividend has not realized. Though the number of nuclear weapons of the two largest nuclear weapon holders—Russia and the United States—was reduced but then the reduction process came to a complete halt. The number of states possessing nuclear weapons has almost doubled against the background of further modernization of such weapons, lowering the threshold of their possible use and the increase in nuclear weapon spending. The non-proliferation regime is gradually weakening. JAPANESE | SPANISH

One of the contributions of non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) to reducing nuclear proliferation has been the establishment of nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs) that are recognized as practical contributions to non-proliferation and confidence building. The main elements of NWFZs are: agreement among members of a particular region not to acquire nuclear weapons or allow placing nuclear weapons on their territory, agreement on a verification mechanism and acquiring security assurances from the five nuclear-weapon states (the P5): Russia, the United States, China, France and the United Kingdom.

Issue of correctly defining NWFZs. Article VII of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) makes reference to the right of groups of States (emphasis added by the author) to establish NWFZs[1]. It is understandable that in the late 1960s interest of negotiators of the NPT was to encourage establishing regional zones that would involve many NNWS.

Based on the experience of establishing the first NWFZ in Latin America and in fact encouraged by it, UN General Assembly in 1974 called for a “comprehensive study of the question of NWFZs in all its aspects” to promote the establishment of such zones in other parts of the world. Ad Hoc Group of Qualified Governmental Experts established for that purpose had produced in 1975 a report on the issue.[2] Despite its name, the focus of the study was on regional zones only (known as ‘traditional zones’).

However, at the same time, the study also recognized that life was rich in its diversity and therefore it did not rule out non-traditional cases. Indeed, there can be situations when individual states, due to their geographical location or for some valid political or legal reasons, cannot be part of traditional zones. The question is: Should such cases be regulated and protected by international law? Otherwise, many blind spots and grey areas may appear in the nuclear-weapon-free world that we all are trying to build.

Mindful of that, the report had pointed out that obligations relating to the establishment of NWFZs may be assumed not only by groups of states, entire continents or large geographical regions but even by individual countries.[3]

Having considered the report, the General Assembly in its resolution 3472 (XXX)[4] had defined NWFZs. Regarding the scope of the definition, the Assembly had declared that the definition “in no way impaired the resolutions which the General Assembly has adopted or may adopt with regard to specific cases of nuclear-weapon-free zones nor the rights emanating for the Member States from such resolutions.”[5] Due to differences of views on this issue, the resolution was adopted by a vote of 82-10-36, underlining that the definition did not enjoy universal support.

Based on this regional approach to NWFZs, five traditional zones have been established, i.e. in Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, on the entire African continent and in Central Asia, that include 118 states, making up almost 40% of world population and 60% of UN membership. That is a practical contribution of NNWS to nuclear non-proliferation. Currently, efforts are underway to establish the second generation of regional NWFZs in regions with conflicts or where great powers have geopolitical interests and stakes. They include the Middle East, Northeast Asia and the Antarctic.

Encouraged by the progress in establishing of NWFZs in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia and on the African continent, in January 1997 the General Assembly had asked the United Nations Disarmament Commission (UNDC), its subsidiary organ that considers and makes recommendations on disarmament issues, to help promote the establishment of additional regional zones by elaborating guidelines thereon.

The UNDC adopted in 1999 the guidelines that again underlined that each NWFZ was the product of the specific circumstances of the region concerned and that the guidelines needed to be regarded as a “non-exhaustive list of generally accepted observations in the current stage of the development of NWFZs”[6], hinting thus on the need to look at the issue of defining NWFZs in broader terms.

Mongolia’s experience. During the cold war, Mongolia was an ally of one of the two superpowers and was under its political influence. After the Sino-Soviet border clashes in 1969, the Soviets entertained the idea or made believe of making a pre-emptive strike against Chinese nuclear facilities. The US made it known to the Soviets that such an act would be the beginning of World War III. That response most probably convinced the Soviets to back down.

The main lesson drawn by Mongolia, sandwiched between the Soviet Union and China, was that alliance with a nuclear weapon state and hosting the latter’s bases did not contribute to confidence and made the hosting country a legitimate military target. Mindful of this lesson as well as the agreement between Russia and China not to use territories of neighbouring third states against each other, in 1992 Mongolia declared its territory an NWFZ (meaning a single-State zone) and has since been working to have that status internationally recognized and guaranteed.[7]

Politically, the P5 welcomed Mongolia’s initiative as a peace-loving gesture but in practice were reluctant to support the concept of single-State zones. So as to acquire support for its initiative, in 1997 Mongolia proposed to the UNDC to consider the issue of establishing single-State zones in parallel with elaborating the new guidelines and submitted a working paper thereon[8]. However, the P5 was reluctant saying that doing so would set an unwelcome precedent and also undermine incentives for establishing new regional zones. The P5’s negative position deprived the UNDC to properly consider the issue.

When negotiating a UNGA resolution on Mongolia’s issue the P5 were still reluctant to recognize it as a single-States zone. After some talks, they agreed to recognize Mongolia’s unique nuclear-weapon-free status but not name it a zone[9].

Nearly two decades of talks and negotiations of Mongolia with the P5 at expert and Ambassadorial in bilateral, trilateral formats and with the P5 as a group, and Mongolia’s agreement not to insist on a multilateral treaty on the issue, in 2012 the P5 signed a joint declaration regarding Mongolia’s status in which they pledged to Mongolia, and in fact to each other, to respect its status and not to contribute to any act that would violate it.[10] That was an important step in addressing Mongolia’s concern but the P5 still refused to recognize it as a single-State zone.

It is pertinent to ask the P5, that are permanent members of the UN Security Council that by the UN Charter are entrusted with the primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, what is more important, establishing single-State zones that would contribute to international trust and security or knowingly allow for nuclear blind spots or grey areas to place weapons-related facilities and thus contributing to further distrust. The answer is obvious.

Broader implications of single-State zones

A single-State zone is not only a Mongolia-related phenomenon. It might be established in Nepal or Afghanistan, for example. Thus, when India and Pakistan became de facto nuclear-weapons states in 1998, some South Asian states have developed an interest in the issue. For example, 11-article draft legislation was submitted to the parliament of Bangladesh dealing with a related issue. In Sri Lanka, this idea raised interest as well, at least in the academic circles. In 2016 Iceland’s Parliament declared the country and its exclusive economic zone an NWFZ[11]. With the entry into force of TPNW some states parties to military-political alliances, inspired by some of their peers, might decide to outlaw hosting nuclear weapons during peacetime.

The gap in international law needs to be addressed. P5 reluctance to recognize single-State zones creates a gap in developing international law. The practical legal consequence of such loopholes must be seriously looked into since however effective regional zones may be, in the end, the nuclear-weapon-free world would be as strong as its weakest links. Even in the case of territories south of the Equator which is considered to be 99% covered by NWFZs, in actual fact, it is not so.

Thus, in the Western Pacific, small island states not parties to regional zones and non-self-governing territories (NSGTs) with their vast surrounding ocean spaces should not be excluded from developing a nuclear-weapon-free world. The same can also be said of some other areas south of the Equator.

With the intensification of the arms race, one should not exclude that NWS might not be tempted to use territories of NNWS and NSGTs and place there, if not actual nuclear weapons, then nuclear weapons-related facilities, such as surveillance, tracking, homing or cyber-interference devices, part of command-and-control systems so as to acquire political-military advantages at a time when time and space are becoming important if not determining military factors. Therefore, there is a need for the P5 to make a joint statement (a softer version of assurance) on non-involvement of NNWS in nuclear-weapons support related activities.

Need for a new study on NWFZs. The circumstances mentioned above underline the importance of recognizing single-State zones as essential parts of NWFZs that would not serve as weak links but also allow un-tapping to the fullest extent the potential of NWFZs.

In September 2013 at the High-level Meeting on Nuclear Disarmament, Mongolia proposed to undertake a second comprehensive study on NWFZs in all its aspects[12] by making practical use of the nearly four decades of accumulated state practice, rich experience and lessons learned that would be useful in negotiating the second-generation zones. The study should also address the issue of providing unconditional security assurances by the P5 to the protocols to NWFZ treaties.

Looking to the future, the study should examine the issues of establishing single-State zones and providing NNWSs that are not parties to regional NWFZs with some softer versions of assurances mentioned above until international legally-binding negative security assurances for all NNWSs are negotiated and agreed. In short, it is time to think and act beyond the current practices of NWFZs.

The Conference of nuclear-weapon-free zones and Mongolia (NWFZM) to be held this year just prior to the NPT Review conference provides an opportunity to address these issues that would further strengthen NWFZs and expand the geographical scope of their operation for the cause of peace and greater security. That would be yet another practical contribution of NWFZs to strengthening the non-proliferation regime. [IDN-InDepthNews – 30 April 2021]

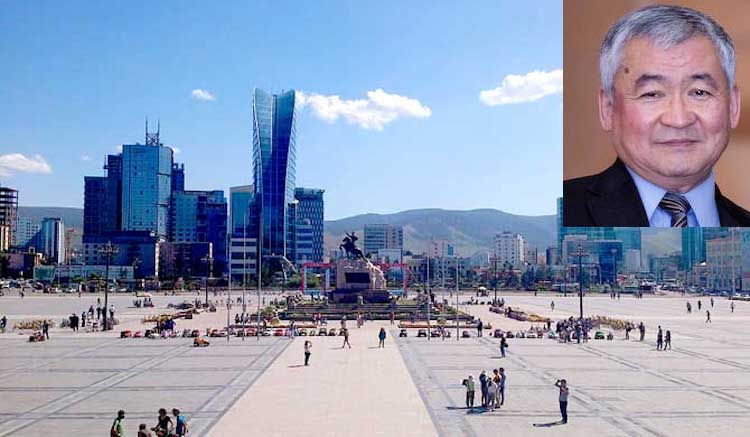

Photo: Dr Jargalsaikhan Enkhsaikhan (Credit: Global Peace Foundation) against the backdrop of Chinggis Khaan (Sükhbaatar) Square in Ulaanbaatar, the capital and largest city of Mongolia. CC BY-SA 4.0

IDN is the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.

Visit us on Facebook and Twitter.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to share, remix, tweak and build upon it non-commercially. Please give due credit.

[1] Article VII: Nothing in this Treaty affects the right of any group of States to conclude regional treaties in order to assure the total absence of nuclear weapons in their respective territories.

[2] UNGA, 30th Session. Official Records. Document No. 27A (A/10027/add.1)

[3] Ibid.

[4] UNGA resolution 3472 (XXX) of 11 December 1975

[5] Ibid.

[6] Report of the Disarmament Commission. General Assembly Official Records. Fifty-fourth session. Supplement No. 42 (A/54/52)

[7] UNGA document A/47/PV.13 of 6 October 1992

[8] UNGA document A/CN/10/195 of 22 April 1997

[9] UNGA document A/RES/53/77 of 12 January 1999

[10] UNGA and SC documents A/67/393 and S/2012/721 of 26 September 2012

[11] Parliamentary resolution on a national security policy for Iceland. Adopted in the 145th Legislative Session, 2015-2016. Parliamentary document 1166-327th matter. No.26/145

[12] See UNGA document A/68/PV.11