Viewpoint by Sergio Duarte

The writer is President of Pugwash. Former UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs.

NEW YORK (IDN) – The contentious start of the 74th Session of the First Committee of the General Assembly last October in New York was a harbinger of the difficulties to be faced in the run-up to the forthcoming 2020 Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and in United Nations multilateral organs devoted to disarmament.

Due to the controversy over the denial of visas to members of some delegations the Committee was only able to complete the general debate and to adopt its program of work two weeks into the session. Delegates of the States concerned engaged in a confrontational exchange of accusations that at one point forced the Committee to face the prospect of an indefinite suspension of its work.

A compromise procedural solution was finally worked out, allowing it to resume the consideration of the items on its agenda and ultimately proceed with the usual adoption of resolutions – some of them repetitive or conflicting.

The possibility of an unprecedented move of the venue of the 2021 session of the First Committee to alternative locations was raised but was averted by a wide margin. The large number of abstentions (72) shows that a majority of States preferred not to take sides in a dispute that reflected mainly the deterioration in the relations between the two major powers.

It must be recalled that earlier in the current year similar problems forced the United Nations Disarmament Commission (UNDC) to work informally instead of holding its regular scheduled session and was responsible for harsh exchanges and dissension at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) for the 2020 NPT Review Conference. The hostile climate prevailing between some key States may prove to be a major factor for the permanence and worsening of the dysfunctional situation in bilateral and multilateral bodies dealing with international security and disarmament questions.

The heated mutual accusations between the delegations involved highlighted questions quite extraneous to the subject matter of the First Committee. The ensuing debate on the substantive items in its agenda, however, showed that while the differences of approach between States that rely on nuclear weapons for security and the rest of the international community remain as acute as ever.

There is growing general concern about the future of the multilateral framework of agreements in the field of disarmament. Many members, including some of the allies of nuclear-weapon States voiced their preoccupation with the erosion of the arms control and non-proliferation architecture, particularly the demise of the Anti-ballistic Treaty (ABM) and the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), as well as with the prospect of a similar fate to befall the Joint Common Program of Action (JCPOA) and the New START Treaty. They urged the adoption of measures to restore confidence in the norms-based international process. Doubts about the effectiveness and validity of existing international law may result in a reinforcement of the trend to replace accepted principles and negotiated agreements by unilateral decisions of the powerful.

The First Committee heard urgent calls for the reaffirmation of the Reagan-Gorbachev mantra that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”. The need for the entry into force of the Comprehensive Test-ban Treaty (CTBT) was emphasized by several speakers, who also commended the progress of the process of signature and ratification of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Others voiced opposition to that treaty by reiterating the opinion that it contradicts and undermines the NPT, although without elaborating or convincingly explaining this position.

The importance of ensuring a consensus outcome of the Tenth Review Conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 2020 was brought up in the debate. The Review Conference is widely expected to promote a rededication to the goals of the NPT as a key multilateral instrument for international peace and security. A number of speakers pointed out that the NPT has not yet made good on its promises.

One of the latter said that “the overall objective of achieving a world without nuclear weapons in the context of the NPT has eluded us for decades”, while another observed that “the NPT’s ultimate purpose—the total elimination of nuclear weapons—fades more into distance with every announcement of plans to stock-up and modernize nuclear arsenals and lower thresholds for the use of nuclear weapons.”

In fact, over the forty-nine years elapsed since the adoption of the NPT the uneven outcomes of the Treaty’s nine Review Conferences held so far indeed suggest a pervasive lack of confidence in the ability of the NPT to deliver on its promises. The longer this state of affairs prevails, the stronger will be the questioning of the NPT as a pact that, in spite of its non-proliferation benefits, has come to be increasingly seen as a means for nuclear weapon possessors to seek the legitimization of their arsenals and justify their possession indefinitely. Measures to ensure that all its provisions – and not just those relating to some aspects – are fully implemented and effectively respected are urgently needed. The Review Conference is the proper forum for this task.

It should be remembered that the NPT was the result of close cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the times of the Cold War. In spite of their mistrust and outright hostility toward each other, their common interest in securing a treaty to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons to as few countries as possible prevailed. They were able to negotiate between themselves and introduce a joint draft of the NPT at the 18-nation Disarmament Committee. As co-Chairs of that body, they together steered the transit of the draft through the Committee and sent it to the United Nations General Assembly for endorsement. Their continuing leadership is a necessary element for the strength and permanence of the NPT.

It is to be regretted, in this connection, that the five nuclear-weapon States recognized by the Treaty have not been able to come up with common proposals capable of strengthening confidence in the NPT and facilitate the reinvigoration of the multilateral treatment of security matters that affect the whole community of nations. Disturbing suggestions for non-nuclear States to abandon the NPT have been made by a few scholars.

The NPT has proven to be resilient throughout its history. Its coming into being was certainly not the only reason why more States did not obtain atomic weapons, as presidential candidate John Kennedy feared in 1961. Nevertheless, it deserves special credit for being instrumental in limiting proliferation to a relatively small number of countries. The initial doubts and hesitations of many members of the international community – expressed in the fact that about one-fourth of the United Nations membership chose to vote against or abstain on Resolution 2373, which commended the Treaty to the signature of States in 1968 – were gradually overcome and the NPT became the most adhered-to instrument in the field of arms control. It stood the test of its indefinite extension in 1995, although it could be argued in hindsight that it might have been wiser for non-nuclear States to have kept the leverage provided by the 25-year intervals prescribed in Article X.2.

There is considerable anxiety about how the current pessimistic atmosphere in the field of nuclear arms control and disarmament will impact the 2020 NPT Review Conference. Many parties fear the negative consequences of two failures in a row. Fortunately, the Third Preparatory Committee succeeded in agreeing on some of the necessary procedural decisions that will permit informal consultations on substance to be carried out in the run-up to the forthcoming review.

Consultations are underway between NAM (the Non-Aligned Movement) and interested governments to find a replacement for Ambassador Rafael Grossi, the President-designate of the 2020 NPT Conference, who was elected to become the new Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency after the passing of Mr. Yukya Amano. On substantive issues, the summary conclusions of the Chair of the Third PrepCom may prove useful as a basis for progress.

The recrudescence of the arms race and its spread into the outer space and cyber domains, as well as the prospect of development of new and more threatening warfare technologies is an underlying concern for many of the parties of the Treaty. It is not difficult to imagine suddenly disabled defensive systems rendered powerless against new delivery vehicles launched from undetectable locations and carrying nuclear warheads travelling at speeds several times greater than that of sound to hit their targets in a few seconds.

In such a scenario, the deterrence value of current nuclear response doctrines would all but disappear. Ironically, the development of such technologies seems able to provide in the near future a solution of sorts to that problem: the use of artificial intelligence would ensure that even in the aftermath of the utter devastation and absence of human hands in the attacked country to press the fatal button, retaliatory nuclear forces would be automatically released to obliterate the adversary and conceivably the rest of the world.

Given the vast destructive power of modern nuclear weapons, “mutual assured destruction” would be replaced by “general assured destruction”, meaning that human civilization as we know it could be wiped out from the face of Earth. Human folly would then accomplish in a matter of a few minutes what unchecked climate change – also a product of human folly – would have taken a few decades to achieve.

It is not too late to try to reverse this ominous trend. Enlightened leadership, particularly from the most armed countries is urgently needed. The United States and Russia must resume the dialogue and constructive cooperation that resulted in the considerable reduction of their nuclear arsenals, even during the Cold War. Further reductions should be negotiated and agreed, leading to the elimination of nuclear weapons altogether. Other nuclear-weapon States should not remain aloof but must also live up to their responsibilities for the improvement of world security conditions. The international community as a whole must remain actively engaged in promoting the observance of disarmament commitments entered into and in seeking solutions to bring to an end the current impasse in the deliberative and negotiating disarmament multilateral bodies. Encouragement and support from civil society and public opinion is vital in this regard.

A constructive initiative in the direction of nuclear disarmament came into being in 2017, when 122 States negotiated and adopted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. (TPNW). Rather than engaging in a fruitless debate on alleged incompatibilities between it and the NPT the international community must work together on enhancing the complementary aspects of both instruments in order to make possible the achievement of the high aspiration of a world free from the threat of all weapons of mass destruction.

As mentioned above, the importance of a solemn declaration by the NPT Review Conference that a nuclear war cannot be won and should never be fought was emphasized at the 2019 Session of the First Committee of the General Assembly. The recommitment by all States parties to the objectives of non-proliferation, peaceful uses and disarmament contained in the NPT would be a welcome departure point for more specific agreements.

For instance, the United States and Russia could agree on the extension of the New START Treaty for five years beyond its expiration date in order to allow for new negotiations on further reductions of their nuclear arsenals. All five nuclear weapon States Parties to the NPT could also: a) pledge to freeze technological developments in nuclear weapons and other methods of warfare; b) agree to negotiate and adopt new confidence-building measures aimed at reducing the risk of a nuclear conflict by design or accident; and ensure the revitalization of the United Nations disarmament machinery, in particular the Conference on Disarmament by starting substantive negotiations on existing proposals. Additionally, the NPT Review Conference could address the significance of the entry into force of the Comprehensive Test-ban Treaty (CTBT) to the realization of the objectives of the NPT.

The NPT is a crucial piece in the multilateral arms control architecture. Despite perceived shortcomings its permanence is necessary in the present international conjuncture. It has successfully helped to prevent proliferation, duly recognized the right of all States to the peaceful uses of atomic energy and holds the promise of the elimination of nuclear weapons. Furthermore, the NPT is the only instrument that legally binds the nuclear armed States to work in good faith toward nuclear disarmament. It is imperative that all its Parties join efforts at the Review Conference to push forward the longstanding aspiration of the international community as a whole to realize the full potential of the NPT and pave the way to a world without nuclear weapons. [IDN-InDepthNews – 21 November 2019]

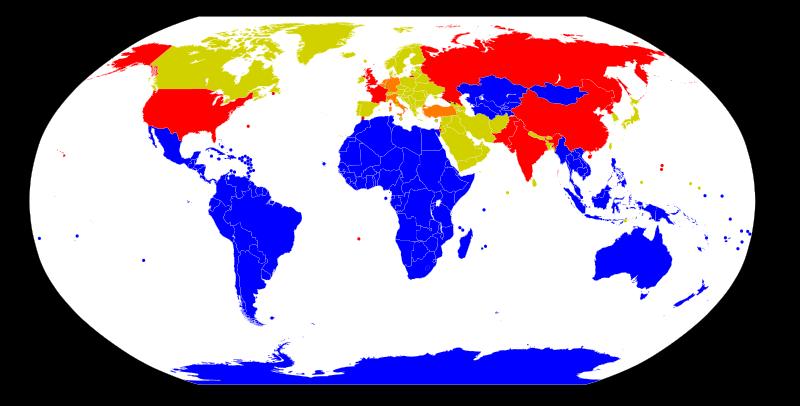

Image: Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (Blue); Nuclear weapons states (Red); Nuclear sharing (Orange); Neither, but NPT (Lime green). CC BY-SA 3.0