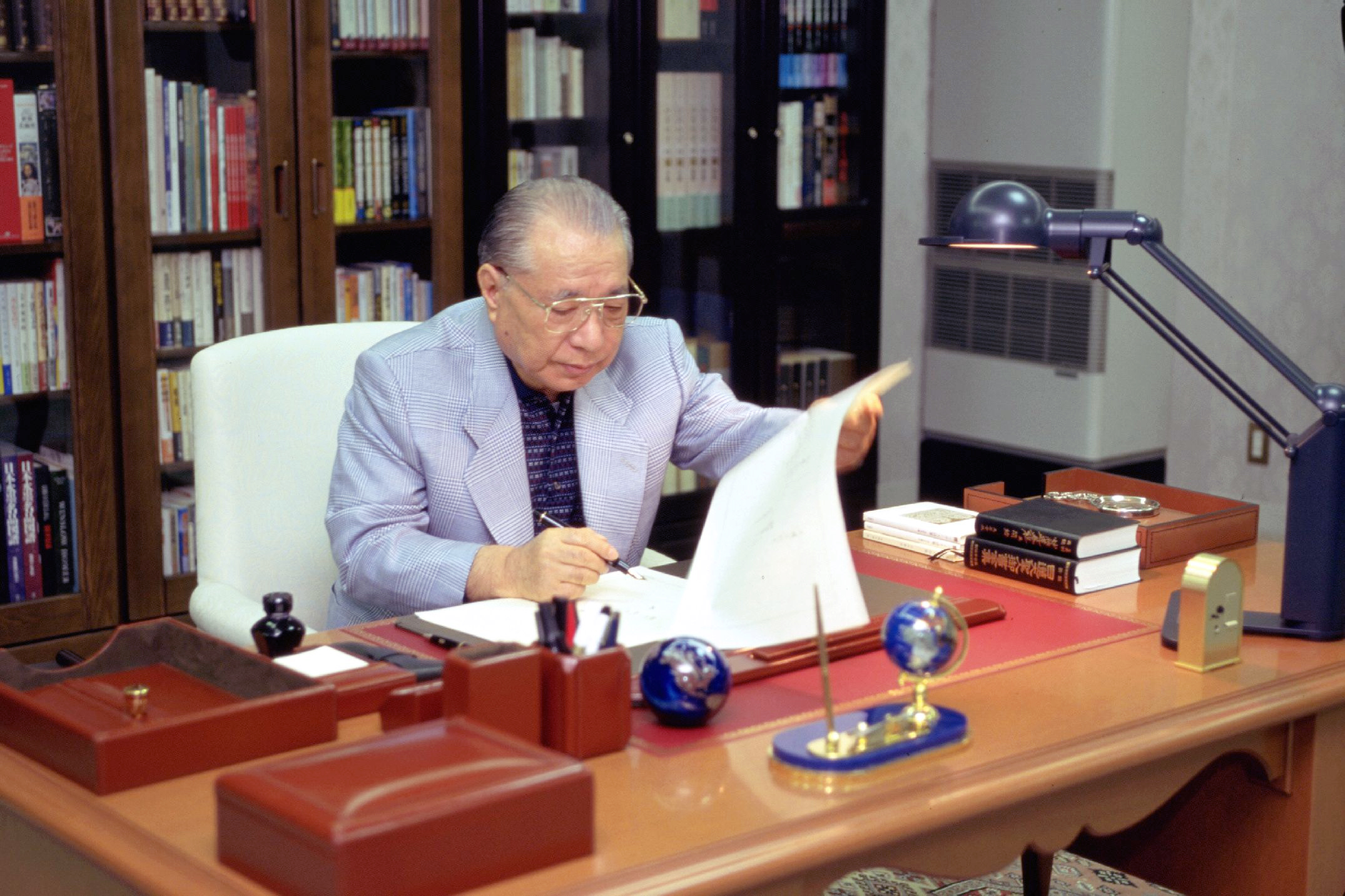

Daisaku Ikeda is a Japanese Buddhist philosopher and peace-builder and president of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI) grassroots Buddhist movement (www.sgi.org). The full text of Ikeda’s 2014 Peace Proposal can be viewed at http://www.sgi.org/sgi-president/proposals/peace/peace-proposal-2014.html.

TOKYO, Mar 29 2014 (IPS) – This past February, the Second Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons was held in Nayarit, Mexico, as a follow-up to the first such conference held last year in Oslo, Norway. The conclusion reached by this conference, on the basis of scientific research, was that “no State or international organisation has the capacity to address or provide the short and long term humanitarian assistance and protection needed in case of a nuclear weapon explosion.”

As this makes clear, almost 70 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, humanity remains defenceless in the face of the catastrophic effects that any use of nuclear weapons would inevitably produce.

Since May 2012, a succession of four joint statements warning of the dire humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons have been issued. These statements have drawn support from a growing number of states; the Nayarit conference was attended by the representatives of 146 countries.

In summing up the outcome of the conference, the Chair stressed the need for a legal framework outlawing these weapons, whose very existence is contrary to human dignity, stating that the time has come to initiate a diplomatic process to realise this goal. It is highly significant that three-quarters of the member states of the United Nations have expressed their shared desire for a world without nuclear weapons in this way.

Regrettably, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, the nuclear-weapon states recognised under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), did not attend this meeting. What is needed most at this juncture is to find a common language shared by the countries signing these joint statements and the nuclear-weapon states.

The movement to focus on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons has emerged against the backdrop of grassroots efforts by global civil society calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Crucially, this has included the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who have long raised their voices in the cry that no one must ever again experience the horror of nuclear war.

On the other hand, the experience of being in possession of the “nuclear button” that would launch a devastating strike has steadily impressed on several generations of political leaders in the nuclear-weapon states the reality that nuclear weapons are unlike other armaments and cannot be considered militarily useful weapons. This has served as a restraint against their use.

In this sense, the two sides share a sentiment that can bridge the gulf between them – the desire never to witness or experience the catastrophic humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons. This can serve as the basis for a common language with which to explore the path towards a world without nuclear weapons.

I have repeatedly called for a nuclear abolition summit to be held in Hiroshima and Nagasaki next year in 2015, the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of those cities. I hope that representatives of the nuclear-weapon states, the countries that have signed the Joint Statement on the Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weapons, as well as representatives of global civil society and, above all, youthful citizens from throughout the world, will gather in a world youth summit for nuclear abolition to adopt a declaration affirming their commitment to end dependence on nuclear weapons and bring the era of nuclear weapons to a close.

In this connection, I would like to offer some concrete proposals.

The first is for a nuclear weapons non-use agreement. One means of achieving this would be to place the catastrophic humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons use at the centre of the deliberations for the 2015 NPT Review Conference. Such an agreement would advance the implementation of Article VI of the NPT, under which the nuclear-weapon states have committed to pursuing nuclear disarmament in good faith.

Regions such as Northeast Asia and the Middle East, which are not currently covered by nuclear-weapon-free zones, could take advantage of a non-use agreement to declare themselves “nuclear weapon non-use zones,” as a preliminary step to becoming nuclear-weapon-free. It is my strong hope that Japan – which signed the most recent iteration of the joint statement on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons even while remaining under the nuclear umbrella of the United States – will reawaken to its responsibility as a country that has experienced atomic weapons attack. Japan should play a leading role in the establishment of such a non-use agreement and non-use zones.

In parallel with such efforts within the existing NPT regime, I would also call upon the international community to fully utilise the process now developing around the successive joint statements to broadly enlist international public opinion and catalyse negotiations for the complete prohibition of nuclear weapons.

This could take the form of a treaty expressing the commitment, made in light of the humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons, to the future relinquishment of reliance on these weapons as a means of achieving security, coupled with separate protocols defining concrete prohibition and verification regimes. Such an approach would mean that even if the entry into force of the separate protocols took time, the treaty would express the clear will of the international community that nuclear weapons have no place in our world.

This coming April 11-12, the Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Initiative will convene in Hiroshima, attended by the foreign ministers of 12 states. From April 28, the NPT Review Conference preparatory committee will meet in New York. These are opportunities for global civil society to arouse international public opinion and to accelerate progress towards the elimination of nuclear weapons.

The work of building a world without nuclear weapons signifies more than just the elimination of these horrific weapons. Rather, it is a process by which the people themselves, through their own efforts, take on the challenge of realising a new era of peace and creative coexistence. This is the necessary precondition for a sustainable global society, a world in which all people – above all, the members of future generations – can live in the full enjoyment of their inherent dignity as human beings.