By Sergio Duarte and Jenifer Mackby*

On February 14, 2017 the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean – Treaty of Tlatelolco – celebrated its 50th anniversary. The Treaty prohibits the testing, use, manufacture, production or acquisition of nuclear weapons. All 33 countries in the region are party to it. This article casts a close look at the vital importance of the treaty.

NEW YORK (IDN-INPS | TRANSCEND Media Service) – As the first of its kind in a populated area, the Treaty made a fundamental contribution to both global and regional disarmament, peace and security. It includes a number of innovative provisions, such as indefinite duration, prohibition of reservations, a definition of nuclear weapon, a commitment by nuclear-weapon States to respect the militarily denuclearized status of the Zone through negative security assurances and the engagement of its Parties to utilize nuclear energy exclusively for peaceful purposes. JAPANESE

The Treaty enshrined the principle that nuclear weapon free zones do not constitute an end in themselves, but rather a means to achieve general and complete disarmament and particularly nuclear disarmament. Last but not least, it also upholds the principles of equality of States and of non-discrimination among its parties.

OPANAL is the international organization responsible for ensuring compliance with its obligations. In 1992 the IAEA was given exclusive authority to carry out inspections. Because all Latin American and Caribbean countries have also adhered to the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), they are subject to the IAEA safeguards provided in its Article III. They have also signed and ratified the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Moreover, under a Quadripartite Agreement, Brazil and Argentina are subject to inspections by the IAEA and ABACC, an Argentine-Brazilian agency established in 1991.

Over time, other regions of the world emulated the Latin American example: there are now four other zones free of nuclear weapons, in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Africa and Central Asia. A total of 113 countries are parties of these zones, besides Mongolia, whose territory was recognized in 1998 by the United Nations as free of such weapons. The majority of them are located in the Southern Hemisphere, making it virtually a nuclear-weapons free hemisphere.

The genesis and the success of the negotiation of the Treaty of Ttalelolco owe much to the common Iberian origin of the Latin American countries and their diplomatic tradition, peaceful coexistence and cooperation, and faith in international law and in negotiating mechanisms to deal with the problems of the region.

In 1962 the Brazilian representative to the United Nations General Assembly, Afonso Arinos de Melo Franco, proposed for the first time the establishment of a zone free of nuclear weapons in the Latin American space. A few weeks later, the international crisis resulting from the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba contributed decisively to general support for the idea. Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador, together with Brazil, introduced in 1963 a draft resolution proposing the creation of the Zone.

In the following year the Presidents of these four countries, plus Mexico, announced formally their decision to negotiate and sign an international instrument to bring about the denuclearization of the Latin American continent. Negotiations started in 1964 in Mexico City and concluded successfully in 1967 with the signature of the Treaty, which entered in full force for all its 33 Latin American and Caribbean parties in 2002. Mexican Ambassador Alfonso Garcia Robles was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1982 for his outstanding role in the negotiating process and for his achievements in favor of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation.

Under Protocol II of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, the five nuclear weapon States (declared by the NPT) undertook to respect the nuclear-weapon free status of the Latin American and Caribbean zone and to provide security guarantees to its Parties. Upon ratifying this Protocol, some nuclear-armed States made unilateral interpretative declarations regarding their commitments.

The Parties to the Treaty consider such interpretations incompatible with the purpose and spirit of the Protocol and have requested their review or withdrawal because they can be understood as permitting the transit of nuclear weapons within the zone of application of the Treaty as well as the use or threat of use of such weapons in certain circumstances.

It is important that Parties to the Treaty and Parties to the Protocols share a common understanding on these issues, and for this reason OPANAL is consulting with the nuclear-weapon States and other nuclear-weapon free zone organizations in order to arrive at common positions on questions of mutual interest.

It is interesting to note that 29 years before the conclusion of negotiations in 1996 of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), a broad prohibition on testing nuclear weapons was included in the Treaty of Tlatelolco. This highlights the fact that the CTBT is still not formally in force. It is imperative that the eight remaining States whose ratification is necessary for entry into force do so. Like the five international treaties establishing nuclear weapon free zones, the CTBT is a key element in the effort to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

The 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Tlatelolco is an auspicious occasion that coincides with the beginning of negotiations on a ban on nuclear weapons, following a historic 2016 decision at the United Nations. The successful outcome of these negotiations would go a long way towards the fulfillment of a longstanding objective that most members of the international community have been pursuing since the Charter of the United Nations was signed in 1945.

Similarly, the adoption by all States of effective measures to ensure the security of nuclear materials is essential in the effort to avoid the proliferation of nuclear weapons. The elimination of nuclear arms forever is an urgent and vital task to prevent a nuclear catastrophe and guarantee the survival of the human race.

*Sergio Duarte is Brazilian Ambassador, former United Nations High Representative for Disarmament Affairs; former Chairman of the Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons; former President of the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Jenifer Mackby – Senior Fellow, Federation of American Scientists. This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 13 February 2017. [IDN-InDepthNews – 13 February 2017]

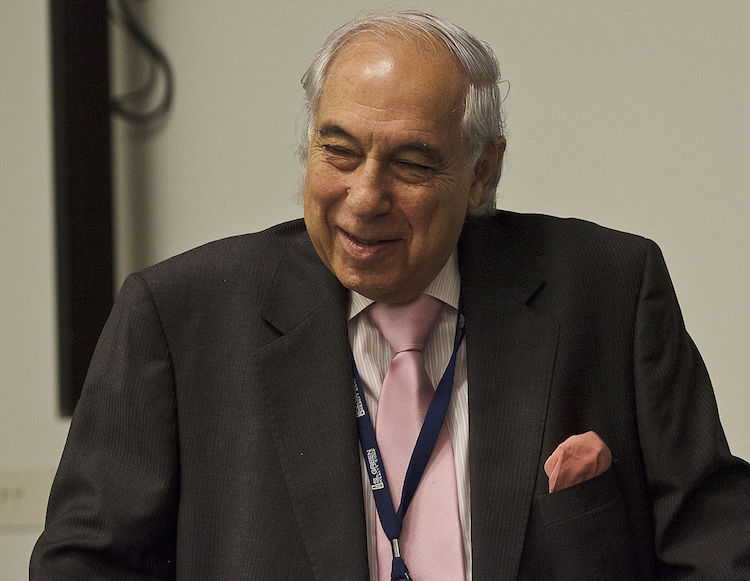

Photo: UN High Representative for Disarmament Sergio Duarte at the Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty on 23 September 2011. Credit: James Leynse | CTBTO Preparatory Commission