Viewpoint by Jonathan Power*

LUND, Sweden (IDN) — Just before he died at the end of the twentieth century, the great philosopher Isaiah Berlin said, “It was the worst century that Europe ever had. Worse, I suspect, even than the days of the Huns. And why? Because in our modern age nationalism is not resurgent; it never died. Neither did racism. They are the most powerful movements in the world today cutting across many social systems”.

In his book “Pandemonium”, the late Harvard professor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, observed that “there are just seven states on earth which both existed in 1914, the year when World War 1 began, and have not had their form of government changed by violence since then”. These are the U.S., Britain, Australia, Canada, Switzerland, Sweden and New Zealand.

“The defining mode of conflict in the era ahead is ethnic conflict”, wrote Moynihan. “It promises to be savage. Get ready for 50 new countries in the world in the next 50 years. Most of them will be born in bloodshed”.

This hypothetical gathering speed of ethnic self-determination provoked Warren Christopher, the US Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton, to throw up his hands in despair, “If we don’t find some way that different ethnic groups can live together in a country how many countries will we have? We’ll have 5,000”.

But what’s the problem? Let a thousand flowers bloom. That, I’m sorry to say, is simplistic. We have to move to stop it happening. The difficulty is the human psyche that makes getting from A to B without war so very difficult. The trouble is that, as in ex-Yugoslavia in the 1990s and in today’s Somalia, Myanmar, Syria and Yemen, neighbouring, but larger and more dominant ethnic groups, don’t want smaller groups moving off into autonomy or independence, cutting their country down to size. And even if they succeeded in doing it would they be recognised by the rest of the world? Recognition, as we found over Kosovo, is considered one of the most difficult topics in international law.

The UN Charter recognises the “self-determination of peoples”. Yet because it implies a significant erosion of the long-held principle of sovereignty, applying it and accepting it has been a divisive issue among international law scholars.

By and large, in most cases, the community of nations has worked from the opinion of the League of Nations when, in 1920, it investigated the request of the Swedish-speaking inhabitants of the Aaland Islands in the Baltic to be allowed “self-determination” from Finland. “To concede to minorities”, the League’s advisors concluded, “either of language or religion or to any fractions of the population, the right to withdrawal from the community to which they belong, because it is their wish or their grand pleasure, would be to destroy order and stability within states and to inaugurate anarchy in international life”.

The Big Five on the Security Council united

This is why the British government supported, in the face of a big outcry at home, the right of Nigeria to put down the bloody revolt in its dissident state of Biafra in the 1960s. Today it is why the Big Five on the Security Council are united in insisting on the territorial integrity of Iraq, Syria and Somalia, even if it defies common sense—as with the Kurds, the largest group of people without a country.

But there is obviously a change afoot in attitude. The US and the EU fought hard for the independence of Kosovo, despite opposition from Spain and Russia. The Spanish government is fearful of undermining its stand for unity in the face of Basque terrorists seeking independence and the vigorous independence movement in its province of Catalonia. For its part Russia voted against independence for Kosovo, arguing if that were done other minorities elsewhere in the world would demand the same, yet a few years later Russia invaded Crimea to break it off from Ukraine. One wonders if Russia would have invaded if it didn’t have the Kosovo precedent to justify its action. Maybe not.

How far will the West change its 1920 stance? Once the ball starts to roll, where does it end as Mr Christopher warned? Ethnic conflicts do not require great differences; small will do—what Freud called “the narcissism of minor differences”.

Should the UN recognize the Polisario struggle against Morocco in its quest to rule West Sahara or the Chechnyan rebels in Russia, the rebellion of the Shan people in Myanmar, the people of Idlib, besieged by the Syrian army, or those fighting for the independence of a part of the northeast of India? The list is a long one.

My own long-held suggestion for what might be a growing problem is the establishment of an International Court of Ethnic Disputes.

A nation being rent asunder or an ethnic group under threat could come to the court and ask a ruling on whether the principles of the Declaration of Human Rights were being followed. Are the boundaries of the province fair? Are the rights of language, education and political representation given to the minority group by the majority reasonable? Are there reforms of law or administration that the court could suggest to make the situation more equitable?

In effect, this is what the mediators did with the Aaland Islands dispute in the 1920s. At the time it was a big issue. Today it is not. The island remains Finnish but the rights of the islanders to use the Swedish language were reinforced.

A Court of Ethnic Disputes could save the twenty-first-century much bloodshed. There is no need for 50 new disputes or 50 new countries.

* About the author: The writer was for 17 years a foreign affairs columnist and commentator for the International Herald Tribune, now the New York Times. He has also written many dozens of columns for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times. He is the European who has appeared most on the opinion pages of these papers. Visit his website: www.jonathanpowerjournalist.com [IDN-InDepthNews — 20 July 2021]

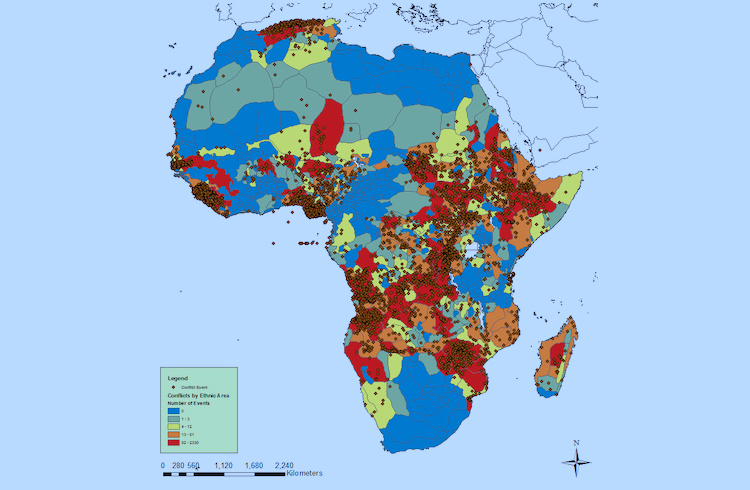

Image: Conflicts in Africa by ethnic region. Source: Good Governance Africa