By Neena Bhandari

SYDNEY (IDN) – Violence is one of the most pressing issues, especially in the highlands, of Papua New Guinea (PNG) – one of the world’s most ethnically and linguistically diverse nations.

“Increased access to high-powered guns such as military style M16s and home-made shotguns, and the breakdown of traditional rules of warfare, has amplified the effects of violence, resulting in dozens – if not hundreds – of violent deaths and thousands of displacements each year, especially in the Highlands,” says International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) chief official in PNG, Mark Kessler. ”We are seeing wounds that one would see in war zones.”

The Pacific island country is divided into four regions – Highlands, Islands, Momase and Papua Region – and 22 province-level divisions: 20 provinces, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville (ARB) and the National Capital District (NCD). Tribal fighting is most prevalent in the Highlands, where it is relatively easy to hire guns and people to fight.

“The economic boom from natural resource extractions and [the country’s] liquid natural gas project has led to an influx of money in the Highlands, but there is no flourishing economy for people to invest their money. So, when people have money, especially men, they buy weapons as it gives them power, or engage in the marijuana trade”, says Kessler.

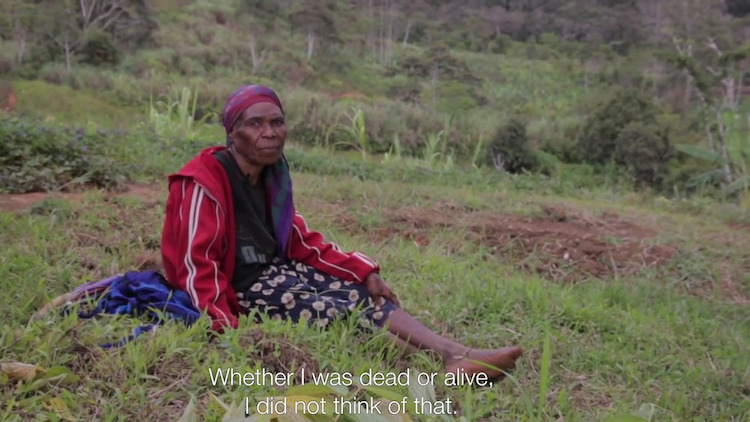

Improved modes of transport and mobile phones have further made it easier to coordinate attacks and for violence to spread. The ICRC has documented the humanitarian consequences of modern-day tribal fighting in PNG and initiatives being undertaken by local and international organisations to mitigate the impacts of the violence in a short film, Spears to semi-automatics: The human cost of tribal conflict in Papua New Guinea.

“Traditionally, fights were over pigs, women and land,” notes Kessler. Now fights are often “sparked by minor disagreements, such as a fight over a mobile phone, where one person slashes the other with a bush knife and the latter retaliates by burning the house and 10 days later you have displaced families and several hundred houses burnt. Sometimes, there can be grave issues relating to land disputes, resources or community grievances against sorcery or sexual violence.”

Adding that “today, the rules of conflict – Don’t kill civilians and children, don’t rape women, don’t burn school and hospitals or threaten health workers – are less respected,” Kessler stresses that “sexual violence has increased in tribal fights.”

The ICRC has been training clinical staff in treating sexual violence and rape as a healthcare issue, and helping to build a better referral system.

“Access to healthcare is not easy and women do not necessarily understand that they should be taking medication to protect against risk of hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS, contraceptive pills and vaccination,” Kessler told IDN. “The risk that they usually see is pregnancy. Most women don’t talk about it. When they do go to the police or the health posts, it is to get certification that they have been raped so that they can ask for compensation from the perpetrator.

“But the victim doesn’t get compensated, it is her husband or brother or father. The women continue to live in the same village, communities, sometimes houses, as the perpetrator.”

A Médecins Sans Frontières report titled Return to Abuser, released in March 2016, identified a lack of appropriate training and an under-staffed police force, which resulted in abusers being rarely brought to justice. The report’s main message was that gaps in services and protection systems must not force survivors to remain with or return to their abusers to experience repeated, worsening violence.

When it is election time – the most recent were held from 24 June to 8 July 2017 – tensions during polling, irregularities in vote counting and the announcement of winners erupts into widespread violent protests, leading to burning of buildings and deaths.

It is the safety and security of women that is particularly at risk during elections. “Candidates’ supporters indulge in bribing, harassing and even raping. Some political parties, especially those in the Highlands, use rape as a weapon against their opponents during elections,” says Helen Samu Hakena, co-founder of Leitana Nehan Women’s Development Agency (LNWDA) and member of the Pacific Women Against Violence Network which is administered by the Fiji Women’s Crisis Centre (FWCC).

Born as a ‘woman chief’ in Gogohe village on Buka Island in ARB, Hakena has suffered and witnessed violence at close quarters, which has made her an ardent advocate for justice, peace building and women’s rights.

“Colonialism and the war have eroded women’s traditional leadership, conflict resolution and custodial roles,” she told IDN. “Domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, verbal and emotional abuse of women is all too common. Through our advocacy work we are trying to re-establish women’s roles. By putting women in positions of power, we can break this cycle of violence. We have been successfully lobbying for more women in government.”

There are 44 political parties in PNG, but few parties have gender equity and equality in their election manifestos. In 2012, there were 135 women candidates contesting the elections and only three women were elected to the National Parliament.

This year that number increased to 165, but the percentage of women candidates is far short of what some of the other Asia-Pacific countries have achieved and, despite a record number of women candidates standing in this year’s general election, there will be not a single female MP.

“Women still face a number of challenges,” United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) senior electoral advisor Ray Kennedy told IDN. “There are reports of women being browbeaten into not running or heckled for being a candidate. The electoral office has been training poll workers to establish separate queues for men and women so that women feel safer going to the polls.”

The unicameral National Parliament of PNG has 111 seats, 89 members are elected from single member open constituencies, 20 from province-level constituencies, one from ARB and one from NCD. Under the limited preferential voting system, voters list their top three choices.

“The number of candidates contesting the elections has declined from 3443 in 2012 to 3324 in 2017. Candidate numbers have fallen in the Highlands and Southern Regions, but they have stayed the same in the Islands, and actually increased in Momase”, says Terence Wood, Research Fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy of the Australian National University (ANU).

“Most of the fall in candidate numbers has been driven by a small number of the electorates, some of which had particularly high numbers of candidates in 2012,” Wood told IDN. “The reasons cited for falling candidate numbers was the talk of candidate registration fees rising, which eventually didn’t go up; and sitting Members of Parliament having very high constituency funding and challengers viewing their chances of beating incumbents as too low to be worth the bother.”

For this year’s elections, UNDP coordinated and supported over 100 international electoral observers. Besides the 270 Papua New Guineans fielded by ANU and another contingent of 400 Papua New Guineans from Transparency International PNG, there will be international observers from ANU, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the Australian, United Kingdom, Solomon Islands and New Zealand High Commissions, the United States, France, Israel, Japan, Republic of Korea, the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) and the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat.

According to Kennedy, “election observation helps deter, though not completely preclude, malfeasance in the electoral process.” In fact, the Commonwealth observer interim report noted “widespread” electoral roll irregularities and four people were reported to have died in election-related violence in the capital of Enga province. [IDN-InDepthNews – 29 July 2017]

Photo: Spears to semi-automatics: The human cost of conflict in Papua New Guinea Highlands. Credit: ICRC