By Liam O Connor, Francisco Martes Porto Macedo and Omar Siddique

BANGKOK, Thailand (IPS) – Asia and the Pacific is home to 54 per cent of the world’s urban population, who are disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (ESCAP, 2023; IPCC, 2022). Why then, do climate action projects in cities commonly face delays in implementation?

Crucial new developments in mitigation and adaptation including: renewable energy, public transport, and nature-based solutions, are needed to safeguard the lives of billions, yet many struggle to secure sufficient funding. In fact, studies estimate that, globally, there is a $6-$12 trillion gap in annual funding for climate and resilience investment (Buchner and others, 2023).

Of the funding that does come in, only 10 per cent goes to adaptation projects (Negreiros and others, 2021), highlighting a real need to address human vulnerability in cities. So how can cities draw from greater sources of private and public investments for climate action?

Perhaps one solution is matchmaking – but not the kind you’re thinking of.

Urban-Act is an international project funded by the Government of Germany’s International Climate Initiative (IKI) with ESCAP as an implementing partner that seeks to accelerate access to urban climate finance. Urban-Act facilitates project preparation for cities, helping move their projects along the urban climate finance value chain so they can attract public or private finance.

This is followed by city climate finance matchmaking, where cities are connected with potential investors through in-person events or online platforms. This process is explored in detail in ESCAP’s 2023 working paper, Enabling Innovative Investments.

The paper highlights how project preparation and matchmaking can unlock the potential of public-private partnerships (PPPs) to bridge the climate finance gap and accelerate climate action in cities. However, several challenges must be addressed.

These challenges include:

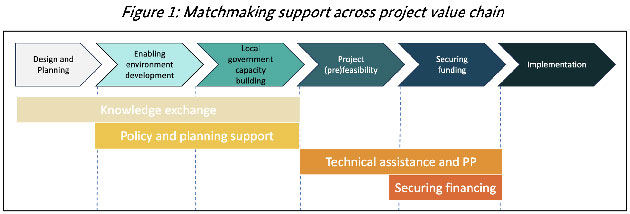

The same paper highlights some potential solutions for providing cities with more effective support. As investors often avoid climate projects due to large upfront costs and higher perceived risks, cities can seek blended finance between private and public investors, using public grant money to prepare well-developed projects, making them attractive to private investors due to smaller ticket sizes (the amount of capital for each share) who can then fund later stage implementation (see figure 1 to visualize project value chain).

Another solution involves financial aggregation. Here matchmaking programmes can consider working with multiple cities with similar projects to better replicate interventions, and/or they could compile many small projects from one city into one portfolio, increasing funding as they leverage of economies of scale and reduced transaction costs.

Enabling Innovative Investments (2023) lists a series of recommendations for successfully employing these solutions and ultimately enabling effective city matchmaking. They range from encouraging impact assessments for learning from mistakes to engaging in investor consultation early to align projects with investor criteria.

• To achieve blended financing:

• While financial institutions should support cities by:

• To valorize financial aggregation:

• To improve the effectiveness of matchmaking efforts in the long term:

Despite the uneven split of finances that goes towards mitigation projects, current trends show we are straying away from the 1.5°C warming target globally agreed upon at the Paris Agreement in 2015, emphasizing just how important it is that we accelerate climate finance in cities, particularly for adapting to the adverse effects of climate change that are expected to increase with time.

Projects such as Urban-Act that make use of project preparation support and city matchmaking, along with the recommendations developed in the Enabling Innovative Investments (2023) paper, can help bridge the significant investment gap for climate action, making way for more sustainable and climate resilient cities.

Liam O Connor, is Intern, Environment and Development Division, ESCAP; Francisco Martes Porto Macedo is Senior Program Associate, Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance, Climate Policy Initiative; Omar Siddique is Economic Affairs Officer, ESCAP.

INPS Japan/ IPS UN Bureau Report