‘After Christ’s example, I forgive my persecutors. I do not hate them. I ask God to have pity on all, and I hope my blood will fall on my fellow men as a fruitful rain.’

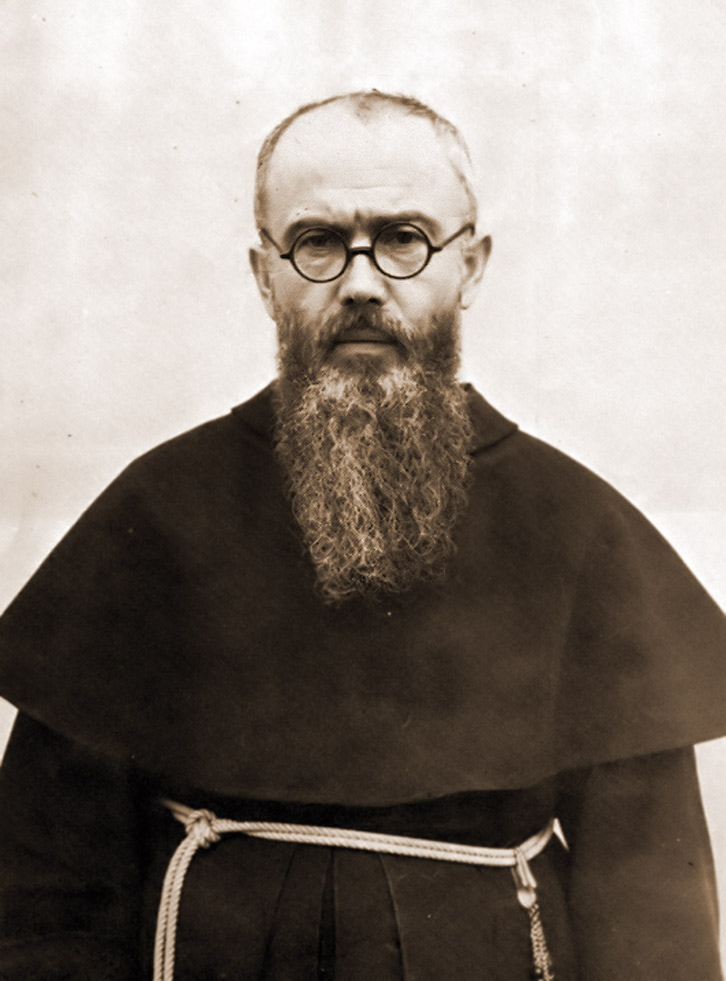

NAGASAKI (INPS Japan) — High above the city of Nagasaki, I walk a Way of the Cross in the steps of St. Maximilian Kolbe, who founded a monastery here in 1931. The lush mountainous area is marked by a grotto reminiscent of Lourdes, built by the Polish Franciscan saint to honor the Blessed Mother and sanctify the place where he lived for five years, until called back to Poland. |JAPANESE|KOREAN|

Americans associate Nagasaki with the atomic bomb, dropped by a U.S. B-29 on Aug. 9, 1945. In Japan, however, the region is also synonymous with Catholicism. Missionaries brought the faith to Japan’s southern ports in the mid-1600s. Nagasaki’s Christian community grew so quickly it was known as “Little Rome” among traders at the time.

A visit to Nagasaki is an immersion in Japan’s Catholic story — at once, brutal, mystical, and still very alive. It is also the tragic history of a continuous martyrdom.

New Souls and New Martyrs

Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier, became intrigued by Japan just a few years after Portuguese merchants, blown off course, washed up on the archipelago’s southern tip, “discovering” a beautiful land riven by belligerent warlords — who were most intrigued by the guns on board with the foreigners.

In the two years (1549-51) Xavier lived in Japan, he brought close to 1,000 souls to Christianity. Over the next 30 years, some 200,000 Japanese converted.

One of those was Paul Miki, baptized as a child when his wealthy, powerful family accepted the new religion sweeping southern Japan. He entered the country’s first Jesuit seminary as civil authorities began unfolding an increasingly brutal persecution.

Fearing that Europeans intended to conquer Japan through the Church, the imperial government banished Catholic missionaries in 1587. Many went underground.

Nagasaki remained a major Catholic center because it was the chief port for international trade controlled by a Christian lord, who used harbor dues to pay Jesuits to run schools, poor houses, and churches.

Then an incident involving a Spanish galleon that ran aground, carrying treasure and clergy, infuriated a dictatorial imperial minister. He ordered guards to round up Catholic missionaries and believers, parade them through the imperial city of Kyoto, then march them to Nagasaki — a monthlong journey in mid-winter — for public execution. His objective was a horrifying public spectacle to paralyze conversions.

Miki, age 33, was one of three Japanese Jesuit catechists corralled by imperial guards together with six Franciscan foreign missionaries, and 17 lay Catholics, including three altar boys. A gifted preacher, Miki proclaimed the Gospel message along the length of their via dolorosa despite being mutilated (ear lobes sliced off), tortured, starved and jeered en route.

When the condemned men and boys reached Nagasaki, they were brought to a prominent hill where 26 crosses were ready, and thousands of citizens assembled. Hoisted on the wood with ropes and iron clamps, the martyrs sang and prayed until each was painfully executed by bamboo lances thrust up through their bodies.

Miki’s final words exemplified his holy spirit:

“After Christ’s example, I forgive my persecutors. I do not hate them. I ask God to have pity on all, and I hope my blood will fall on my fellow men as a fruitful rain.”

“But the executions failed because they did not eliminate faith,” explains Jesuit Father Renzo de Luca, director of Nagasaki’s Twenty Six Martyr’s Museum. “People were extremely moved by what they witnessed, and that deepened devotion.”

Believers collected relics, including blood-soaked scarves, displayed at the museum, which was established in 1962 to mark the centennial of Pope Pius IX’s canonization of St. Paul Miki and his companions.

Hidden Christians

When high profile executions proved ineffective against believers, authorities tried more individual approaches, especially once Christianity was banned outright in 1614. Bounties were offered for information on Christians; a higher price was put on the head of a priest (as reflected in Martin Scorsese’s film Silence based on Shūsaku Endō’s historical novel.) Households were required to register with Buddhist temples.

To test whether someone was secretly devout, individuals were required to step on images of Jesus or Mary. These efumi-e are often beautiful bronze images, smoothed by countless feet. In Nagasaki, this was an annual test implemented from 1629 to 1856.

When Catholics were ferreted out, often by their own devotion, torture was extreme: They were boiled alive in hot springs; drowned slowly while tied to stakes; wrapped in mats and burned over fire; lowered upside down into vats of excrement. Execution for Christianity was only canceled in 1805.

Repression drove faith underground. Catholic images and sacramentals were either well hidden, in walls for example, or concealed in plain sight: Small white Buddhist statutes of Kannon, the Merciful One, became stand-ins for Mother Mary, known as Maria Kannon, venerated in secret.

Kakure Kirishitan, Hidden Christians, passed faith down from one generation to the next without priests. Baptism was the sole regular sacrament.

Some 50,000 visitors a year visit the Martyrs Museum — increasingly, pilgrims from Korea. According to Father de Luca, the respective bishops’ conferences of Japan and South Korea made a mutual commitment to increase understanding by encouraging these visits.

Kolbe and Mugenzai No Sono

Polish Catholics seeking places touched by St. Maximilian Kolbe also come.

Amazingly, within a month of his arrival in 1930, Conventual Franciscan Father Kolbe was already printing a Japanese edition of his magazine, Knight of the Immaculate (Knight of Mary-Without-Sin in local translation), the country’s first Catholic magazine.

At first, Kolbe stayed near Nagasaki’s Oura Cathedral, founded by French missionary priests in 1864, to serve a growing community of foreign merchants as Japan reopened to overseas trade.

Father Kolbe was moved by the church’s extraordinary connection to the Hidden Christians: Soon after Oura’s dedication, Father Bernard Petitjean was visited by a group of believers from the Urakami district, descendants of Catholics who maintained the faith for over 250 years. They were farmers, fisherfolk, artisans, and women who recognized the church’s cross — and asked to see a statue of Mary as proof that they shared the same faith.

As a builder of communities, Father Kolbe was determined to start a Franciscan monastery, which he did at Mugenzai No Sono, in the mountainous hills on the outskirts of Nagasaki, where I walked. In this remote place he created a new center of evangelization: Between 1831-36, the number of missionaries grew from five to 20. Circulation of the magazine increased to 70,000; it continues to this day in both Poland and Japan. All this time, Father Kolbe suffered from tuberculosis and was often ill.

The big wooden desk used by the saint is a prominent attraction at the monastery’s small museum — especially since Pope John Paul II sat at this desk when he visited the modest cell.

Georgetown University Professor Kevin Doak, a specialist in modern Japanese history, notes that the saint’s ascetic life in Japan helped prepare him for his martyrdom at Auschwitz.

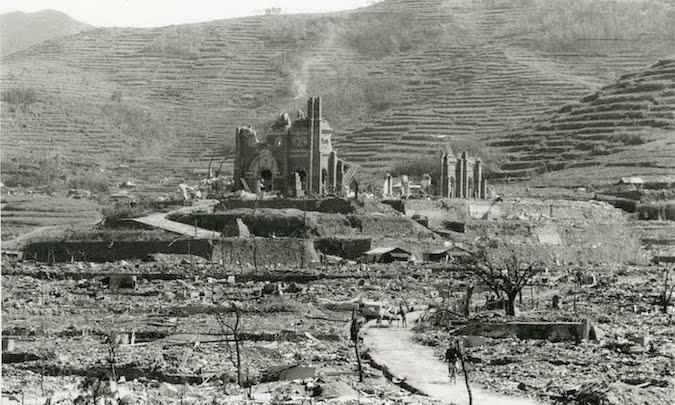

When the atomic bomb detonated over Nagasaki at 11:02 a.m., miles from any military target, it was directly over the Urakami district, where three priests in Asia’s largest Catholic cathedral were hearing confession. It spared St. Maximillian’s sanctuary as it was protected by mountains.

At Ground Zero Stand the Saints

In Peace Park, Nagasaki’s open-air memorial to the atomic bomb’s hypocenter, stands a lonely external pillar, topped by saintly figures, which was part of Urakami Cathedral. The church had been constructed brick by brick between 1895-1917 by the Hidden Christian community when they were finally free. Its presence signifies the centrality of Catholic understanding of the disaster.

Of the citizens immediately erased by the fire ball, heat, and radiation generated by the explosion, 8,500 were Catholic. People like Midori Nagai, a 17th-generation Hidden Christian descendant, burned alive with a rosary in her hand. Only some of Midori’s bones were left — found together with fused beads, a cross, and chain.

By the end of 1945, some 74,000 were dead and 75,000 injured, almost all civilians, as a direct result of this nuclear attack of dubious strategic value.

Preventing Another Nagasaki

“Nagasaki must be the last place exposed to an atomic bomb,” declared Hiroshi Nose, director of the city’s Atomic Bomb Museum, as he tells me how the museum, established in 1955, has evolved.

St. Teresa of Calcutta toured the museum and concluded: All world leaders should see it, because it effectively conveys the massive destructive scope of nuclear weapons and the resulting havoc on human life.

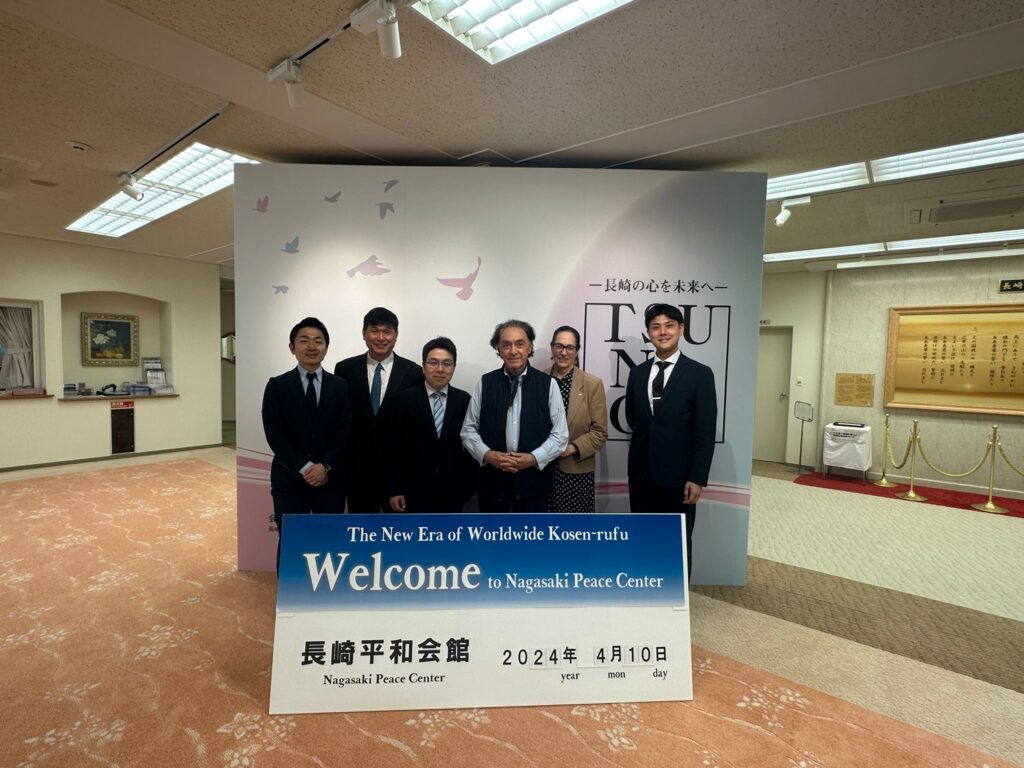

Visiting the Nagasaki headquarters of a Buddhist-inspired cultural organization, Soka Gakkai, I saw a timeline on the wall charting progress toward signatories on a 2017 U.N. convention, the Treaty to Prevent Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), now affirmed by 70 states, including the Holy See.

This treaty is more powerful than the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty but so far, neither Japan nor the United States support it. (Soka Gakkai and Japan’s Association of Shinto Shrines will attend a meeting hosted by the Catholic lay organization Sant’Egidio in Paris in September, where this treaty is on the agenda.)

“Even when tensions between nations are high, citizen diplomacy is crucial. We should expand networks of trust among people,” local Soka Gakkai leader Naotaka Miura told me. Asked his profession he responded simply, “Peace activist.”

INPS Japan/National Catholic Register

Victor Gaetan Victor Gaetan is a senior correspondent for the National Catholic Register, focusing on international issues. He also writes for Foreign Affairs magazine, The American Spectator and the Washington Examiner. He contributed to Catholic News Service for several years. The Catholic Press Association of North America has given his articles four first place awards, including Individual Excellence, over the last five years. Gaetan received a license (B.A.) in Ottoman and Byzantine Studies from Sorbonne University in Paris, an M.A. from the Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy, and a Ph.D. in Ideology in Literature from Tufts University. His book God’s Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy, and America’s Armageddon was published by Rowman & Littlefield in July 2021. Visit his website at VictorGaetan.org. This article was republished with permission from the National Catholic Register.