By Jan Lundius

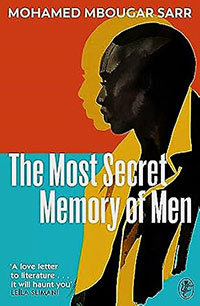

STOCKHOLM, Sweden, Jan 6 2025 (IPS) – In 2021, the Senegalese novelist Mohamed Mbougar Sarr became the first writer from sub-Saharan Africa to be awarded the Prix Goncourt, France’s oldest and most prestigious literary prize.

Literature

His novel, La plus secrète mémoire des hommes, The most Secret Memory of Men, tells the story of a young Senegalese writer living in Paris, who by chance stumbles across a novel published in 1938 by an elusive Senegalese author named T.C. Elimane. This author had once been hailed by an ecstatic Paris press, but had then disappeared from view. Elimane had before every trace of him had vanished, been accused of plagiarism. After losing a legal process connected with the plagiarism charge, Elimane’s publisher had been forced to withdraw and destroy all available copies of The Labyrinth of Inhumanity. However, a few extremely rare copies of the novel remained, profoundly affecting anyone who happened to read them. The novel’s main protagonist (there are several others) eventually became involved in a desperate search for the illusive Elimane, who had left some rare imprints in France, Senegal and Argentina.

A reader of Sarr’s multifaceted, exquisitely written novel is confronted with a choir of different voices mixing, harmonizing and/or contradicting each other. The story turns into a labyrinth, where boundaries between fiction and reality become blurred and lose ends remain unravelled. Sarr moves in an ocean of world literature. It seems as if he has read everything worth reading and allusions are either in plain sight, or remain invisible. Ultimately, the novel investigates the limits between myth and reality, memory and presence, and above all the question – what is storytelling? What is literature? Does it concern the “truth”, or is it constructing a parallel version of reality?

A disturbing issue shimmers below the surface of the intriguing story. Why were two excellent West-African authors before Sarr severely scrutinized and condemned for plagiarism? Why were they accused of not being “African” enough? Are African writers doomed to linger within a shadowy existence as exotic curiosities, judged from the outside by a prejudiced literary establishment, which persistently consider African authors, except white Nobel laureates like Gordimer and Coetze, either as being exotic natives, or epigons of European literature?

The most Secret Memory of Men has a disturbing prehistory, echoing real-life experiences of the Guinean writer Camara Laye and the likewise unfortunate Malian Yambo Ouologuem.

At the age of 15, Camara Laye came to Conakry, the French colonial capital of Guinea, to attended vocational studies in motor mechanics. In 1947, he travelled to Paris to continue his studies in mechanics. In 1956, Camara Laye returned to Africa, first to Dahomey, then to the Gold Coast and finally to newly independent Guinea, where he held several government posts. In 1965, after being subject to political persecution, he left Guinea for Senegal and never returned to his home country.

In 1954, Camara Laye’s novel Le regard de Roi, The Radiance of the King, was published in Paris and at the time described as “one of the finest works of fiction to come out of Africa”. The novel was quite odd, and remains so, particular since its main protagonist is a white man and the story develops from his point of view. Clarence has, after in his home country having failed at most things, recently arrived in Africa to seek his fortune there. After gambling all his money away, he is thrown out of his hotel and in desperation decides to pursue a legend stating that somewhere in the inner depths of Africa a wealthy king can be found. Clarence hopes that this king might provide for him, maybe give him a job, and a purpose in life.

Laye’s novel becomes an allegory for man’s search for God. Clarence’s journey develops into a road to self-realisation and he obtains wisdom through a series of dreamlike and humiliating experiences; often harrowing, sometimes lunatically nightmarish, though the story is occasionally lightened by an absurd and alluring humour.

However, some critics asked if this really was an African novel. The language was beguilingly simple, but the allegorical mode of telling the story made critics assume that it was tinged with Christianity, that the African lore was “superficial”, and the narrative style “kafkaesque”. Even African authors considered that Laye “mimicked” European literary role models. The Nigerian author Wole Soyinka characterized Le regard de Roi as a feeble imitation of Kafka’s novel The Castle, implanted on African soil and within France suspicions soon arose that a young African car mechanic could not have been able to write such a strange and multifaceted novel as Le regard de Roi.

This unkind and even mean criticism became increasingly vociferous, deprecating what was actually an intriguing work of genius. The harassment continued until a final blow was delivered by an American professor. Adele King’s comprehensive study The Writing of Camara Laye did in 1981 “prove” that Le regard de Roi actually had been written by Francis Soulé, a renegade Belgian intellectual who in Brussels had been involved in Nazi- and Anti-Semitic propaganda and after World War II had been forced to establish himself in France. According to Adele King, Soulé had together with Robert Poulet, editor at Plon, the publisher that issued Le regard de Roi, concocted a story that his novel actually had been written by a young African, thus securing its success. To support her theory, Adele King presented an exhaustive account of Camara Laye’s life in France, tracing his various acquaintances and coming to the conclusion that Laye had been paid by Plon to act as the author of Le regard de Roi.

Among other observations Adele King stated that Laye’s novel was of an “un-African nature, with a European sense of literary form”, thus indicating Francis Soulé’s handiwork. This in spite of Soulé’s very meagre literary output (King mentions that he had in his ”youth dabbled in exotic writing”) and the fact that Laye wrote several other, very good novels.

Among other indications that Laye could not have written Le regard de Roi, King argued that the novel’s “Messianic message” sounded false, originating as it did from an African Muslim. She thus ignored that Laye came from a Sufi tradition where similar notions abounded and when it came to the “kafkaesque” flavour of the novel, which is far from being overwhelming – why could not a young African author living in France, like so many others, have been inspired by Franz Kafka’s writing?

Notwithstanding, through these and many other shaky assumptions King concluded that Le regard de Roi had been written by the otherwise almost unknown Francis Soulé and her verdict became almost unanimously accepted. It did for example in 2018 prominently appear in Christoffer Miller’s popular and otherwise quiet good book Impostors: Literary Hoaxes and Cultural Authenticity.

Another resounding condemnation of an excellent West-African author occurred in 1968 when the groundbreaking and original novel Le devoir de violence, Bound to Violence, after a short time of praise was smashed due to accusations of plagiarism. Le devoir de violence dealt with seven centuries of violent history of an African, fictious kingdom (actually quite akin to present-day Mali). In a feverish first-rate, free flowing language the novel does not shy away from depicting extreme violence, royal oppression, religious superstition, murder, corruption, slavery, female genital mutilation, rape, misogyny, and abuse of power. All intermingled with episodes of real love and harmony, but there is no doubt about Yambo Ouologuem’s opinion that a powerful, age-old and corrupt African elite enriched itself and prospered through its collaboration with an equally corrupt and brutal colonial power, all done for their respective gain.

Quite expectedly, Ouologuem arose violent reactions from authors adhering to the concept of négritude, denoting a framework of critique and literary theory developed by francophone intellectuals, who stressed the strength of African solidarity and notions about a unique African culture. Ouologuem provided the négritude movement with his own denigrating term – negraille, accusing négritude authors of ingraining servility and an inferiority complex in Africa’s black population. He accused such authors of depicting Africa as a ridiculous Paradise, when the continent in fact had been, and was, just as corrupt and violent as its European counterpart. Ouologuem also wondered why an African writer could not be allowed to be as critical, outspoken and politically improper as, for example, the French authors Rimbaud and Céline.

The final judgment that befell Ouologuem was delivered by the generally admired Graham Greene, who launched a lawsuit against Ouologuem’s publisher accusing the African author of plagiarizing parts of Greene’s novel It’s a Battlefield. Greene won the lawsuit and Ouologuem’s novel was banned in France and the publisher had to see to the destruction of all available copies of it. Ouologuem did not write another novel, he returned to Mali where he in a small town directed a youth centre, until he withdrew in a secluded Muslim life as a marabout (spiritual advisor).

Considering the framework of Ouologuem’s entire and quite mindboggling novel, Graham Greene’s reaction appears to be petty, if not outright ridiculous. The plagiarism was limited to a few sentences describing a French mansion, which in itself was quite absurd within its African setting, and the description is clearly quoted with a satirical intention (in his novel Greene described a slightly ridiculously decorated apartment of an English communist).

The condemnation of Laye’s, and in particular Ouologuem’s novels may be discerned as an inspiration to Mohamed Sarr’s novel. Sarr writes about a young African author finding himself in a limbo between two very different worlds, Senegal and France, while he has found home and solace in literature, a world within which he has discovered a real gem, his talisman – Elimane’s novel. However, the bewildered young man’s pursuit of the man behind the book turns out to be in vain, and so is probably also his search for himself in this labyrinth that constitutes our life and the world we live in.

Sarr’s novel reminds us of the fate of two other West-African authors before him, who were accused of not being “genuine”, of being “plagiarists”, thus Sarr also succeeds in asking us what is genuine in a floating globalized world?

IPS UN Bureau