By Rodney Reynolds

WASHINGTON DC (IDN) – The 193-member UN General Assembly is to hold two key sessions – in March and in June – in what is expected to be a do-or-die attempt towards the elimination of nuclear weapons worldwide.

“Whether 2017 will be the year that sees nuclear weapons being banned or whether the effort to achieve this gets turned into a form of “fake news” remains to be seen?,” says a sceptical Tariq Rauf, Director of the Disarmament, Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

The dark shadow that looms large over the upcoming General Assembly sessions will be the imposing figure of US President Donald Trump – whose trigger-finger is dangerously close to over 7,000 nuclear weapons, and whose views on nuclear disarmament appear consistently inconsistent, ranging from proliferation to strengthening existing arsenals. HINDI | JAPANESE | CHINESE

The primary aim of the two sessions – scheduled for March 27-31 and June 15-July 7 – is to negotiate “a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination”.

But how realistic and feasible is this – considering the strong opposition it is expected to evoke, specifically from some of the major nuclear powers, including the US, Britain, France, and Russia, who are reportedly lobbying behind-the-scenes to scuttle the conference or cause disarray among non-nuclear states.?

In an interview with IDN, Rauf said all signs indicate that the negotiations will be fraught with deeply-held differences amongst the participating non-nuclear-weapon States.

“There are fears that those NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and allied non-nuclear-weapon States who might participate will run interference and complicate the discussions on behalf of their nuclear-armed masters,” he warned.

Another fault line could be among those non-nuclear-weapon States that want a quick short norm establishing treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons and those that might prefer a more detailed treaty with provisions on verification, said Rauf, former Head of Verification and Security Policy Coordination at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna.

He said civil society participation could be a prominent feature for the first time in multilateral negotiations on a nuclear weapons treaty, and some member states already have given indications of curtailing the influence or involvement of civil society.

John Burroughs, executive director of the Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy (LCNP), told IDN that judging by the organizational meeting held February 16 at UN Headquarters, and attended by over 100 countries, there is considerable momentum toward negotiation of a “treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons, leading to their elimination” – a ban treaty.

The process arises out of the frustration of most non-nuclear weapon states with the failure of the nuclear-armed states to move rapidly and decisively on nuclear disarmament, pursuant to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) obligation to negotiate nuclear disarmament in good faith and UN General Assembly resolutions going back to the very first one, he noted.

For several years, he pointed out, the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Russia, all possessing nuclear weapons, have made clear their opposition to this process. They will not be participating, nor will most states in military alliances with the US.

“In an interesting development, however, China and India were both present at the organizational meeting, and apparently will participate in the negotiations. It would seem they want to demonstrate their commitment to multilateral negotiation of nuclear disarmament, though it is unlikely that they would join a ban treaty at the outset.”

The Netherlands was also present at the meeting, and press reports indicate that Japan, while not at the meeting, is still deciding whether to participate, said Burroughs, who is also Director, UN Office of International Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms (IALANA).

Rauf told IDN this push by a large majority of non-nuclear-weapon States has opened up stark differences not only with States possessing nuclear weapons, but also within the ranks of the non-nuclear-weapon States.

States in nuclear-armed alliances such as NATO and US’ Pacific allies, plus Russia, vehemently oppose any negotiations on a multilateral treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons, while paying lip service to achieving a world without nuclear weapons through an undefined “step-by-step” or “phased” approach with no defined time line.

Three international conferences (Oslo 2013, Nayarit 2014, and Vienna 2015) drew global attention to the deep concern over the pervasive threat to humanity posed by the existence of nuclear weapons and the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any detonation of a nuclear explosive.

Given these risks, the majority of non-nuclear-weapon States stressed the need for urgent action by all States towards achieving a world without nuclear weapons and noted that progress to date towards nuclear disarmament had been very slow.

These States, said Rauf, also highlighted that the NPT had obligated nuclear-weapon States to disarm, but in nearly 50 years of the Treaty this obligation had not been met and there were no signs of it being met.

These States also noted that there was a legal gap regarding the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons, as there was no nuclear disarmament treaty along the lines of the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention that respectively prohibited biological and chemical weapons and mandated their total elimination.

Accordingly, these States proposed a menu of four distinct approaches for the pursuit of a world without nuclear weapons, including: a comprehensive nuclear weapons convention; a nuclear weapon ban treaty; a framework agreement; and a progressive approach based upon building blocks.

Some NATO States on the other hand responded that there was no such legal gap and that the NPT provided an essential foundation for the pursuit of nuclear disarmament.

They stressed that the international security environment, current geopolitical situation, and role of nuclear weapons in existing security doctrines should be taken into account in the pursuit of any effective measures for nuclear disarmament; and as such, a nuclear weapon ban treaty was not in their national security interest.

These States also maintained that a nuclear weapon ban treaty would create confusion as regards implementation of the NPT and complicate fulfilment of the NPT’s nuclear disarmament obligations.

“In fact, a nuclear weapon ban treaty would not affect the NPT,” said Rauf. Those States that are parties to the NPT would still be bound by it and obligated to its full implementation.

A nuclear ban treaty could go beyond the NPT and prohibit possession of nuclear weapons and deployment of nuclear weapons (including in foreign States, as for example in Belgium, Italy, Netherlands and Turkey that host US nuclear weapons under NATO auspices; or as in Japan and South Korea in earlier times).

Just as the 1963 Partial-Test-Ban Treaty banning nuclear test explosions in the atmosphere, outer space and under water does not conflict with the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty banning all nuclear test explosions; similarly the 1968 NPT could not be in conflict with a nuclear weapon ban treaty, declared Rauf.

Burroughs said a ban treaty, as now envisaged, would prohibit the possession and use of nuclear weapons, but not contain detailed provisions regarding such matters as verified dismantlement of nuclear weapons and governance of a world free of nuclear weapons.

The thought is that it does not make sense to negotiate on issues directly affecting states with nuclear weapons without their participation; their expertise, views, and commitment would be needed to satisfactorily resolve the issues.

A ban treaty in this approach would reinforce existing norms as to non-use of nuclear weapons – codifying the incompatibility of use with international humanitarian law governing the conduct of warfare. It would also reinforce existing norms as to non-acquisition of nuclear weapons under the NPT and regional nuclear weapon free zones, he added.

Burroughs said a ban treaty would also build upon, and in a sense unite, the treaties establishing the nuclear weapon free zones. The first of those treaties, the Treaty of Tlatelolco establishing the Latin American and Caribbean zone, celebrated its 50th anniversary on February 14 in Mexico City.

“The significance of a ban treaty may be above all political, a powerful and definitive statement that the status quo as to nuclear weapons is unacceptable, that nuclear weapons must never be used again, and that there must be no more delays in fulfilling the promises of nuclear disarmament made in the NPT and in the UN context, notably the 1978 General Assembly Special Session on Disarmament”.

But depending on the content of the treaty, he pointed out, there will also be specific legal consequences.

For example, there may be a prohibition on financing of nuclear weapons which could significantly affect investment in companies making nuclear weapons, and for states joining the ban treaty, there will likely be a requirement not to assist or cooperate in any way with preparation for use of nuclear weapons by states outside the treaty, said Burroughs. [IDN-InDepthNews – 25 February 2017]

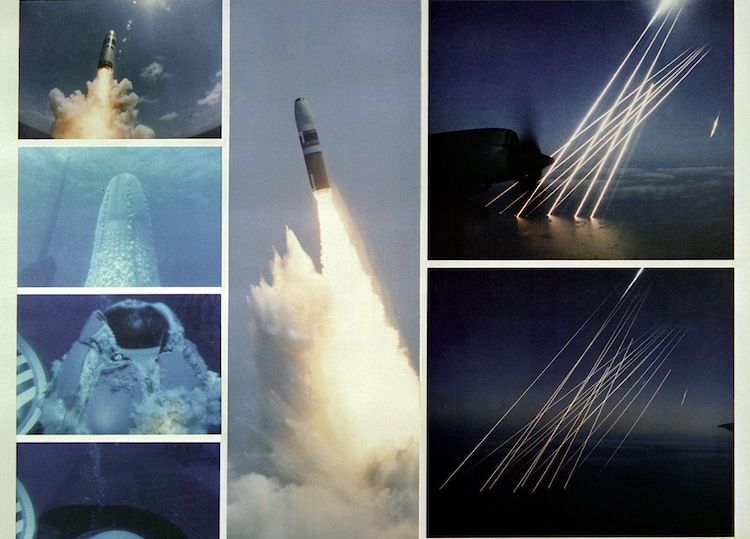

Photo: Montage of an inert test of a United States Trident SLBM (submarine launched ballistic missile), from submerged to the terminal, or re-entry phase, of the multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.